1. Introduction1

In French, as in other Romance languages, many morphological schemas are available to derive nouns from verbs using the same kinds of semantic operations. Notably, -age, -ment, -ion, -ure, -ance, -ade, -erie and -aison suffixations and verb to noun conversion are all able to construct event nouns and sometimes select the same verbal bases, resulting in doublets (1). This overlap in base selection and their ability to form nouns that have similar semantic interpretations have led to considering these schemas as rivals in the derivational system of French.

|

(1) |

rançonner ‘to ransom’→ rançonnage / rançonnement ‘ransoming’ |

|

gouverner ‘to govern’→ gouvernement ‘government’ / gouverne ‘guidance/information’ / gouvernance ‘governance’ / gouvernation ‘government’ |

|

|

décliner ‘to decline’→ déclinement ‘declination’ / déclin ‘decline’ / déclinaison ‘range’, ‘declination’ |

Because of their suspected productivity, especially given the number of triplets that have been identified (Fradin 2014), the competition between -age, -ment and -ion has been extensively studied with the purpose of elucidating the reasons for their coexistence. For the most part, authors have associated their coexistence with an underlying division of labor between the schemas. Research undertaken from the perspective of rule-based representations has primarily focused on finding divergent constraints in base selection and semantic variation between derived nouns. The features that have attracted the most attention are the evaluation of the preferred argument structures of the base verbs as well as the lexical aspect of the input verbs and output nouns (Bally 1965 : 181 ; Dubois 1962 : 29-32 ; Dubois-Charlier 1999 : 20 ; Kelling 2001 & 2003 ; Martin 2010 ; Uth 2008a & 2008b ; Heinold 2010 ; Ferret, Soare & Villoing 2010 ; Ferret & Villoing 2012 ; Uth 2016 ; Fradin 2014 ; Meinschaffer 2016 for a consistent international state-of-the-art).

Recently, the field has taken new directions thanks to an increasing interest in more authentic data made available by web corpora. Whereas previous work mostly relied on constructed examples or lexicographic entries, recent work has opted for data collected from the web (Dal & al. 2004 ; Uth 2010 ; Fradin 2019 ; Dal et al. 2017 ; Dal & al. 2018). This shift has led morphologists to reconsider previous semantic hypotheses : Dal et al. (2018), for instance, provided corpus-based evidence for the lack of preferences in aspectual or argument features between rival -age, -ment and -ion derivatives by analyzing their contexts in web corpora. Simultaneously, rule-based representations have given way to more flexible and quantifiable approaches that envision morphological schemas as sets of interacting constraints in lexematic morphology (for instance, Hathout 2009 ; Roché 2011 ; Roché & Plénat 2014 ; Plénat & Roché 2014 ; Hathout & Namer 2018). Constraints formerly considered as categorical were now regarded as probabilistic and therefore could be identified on multiple levels at the same time (morphological, semantic, syntactic, phonological) by examining the schemas’ input and output tendencies as well as the structures of the paradigms they incorporated (Hathout 2009 ; Bonami & Strnadová 2019).

By considering morphological rivalry from this perspective, quantitative studies have paved the way for new analyses. For example, using word embeddings such as Word2Vec (Mikolov et al. 2013) to investigate the distributional properties of rival schemas, Wauquier, Fabre and Hathout (2018) identified distributional variations between -age, -ment and -ion lexemes. Bonami and Thuilier (2019) proposed a statistical model that predicted the selection of -iser or -ifier for a noun or an adjective and showed that paradigmatic constraints had a strong positive impact on the prediction : -iser favored nominal bases that constructed -ique adjectives (ethnie ‘ethnic group’ → ethnique ‘ethnic’ → ethniciser ‘give an ethnic character’). These results go along with the notion of morphological niche (Lindsay & Aronoff 2013 ; Arndt-Lappe 2014 ; Aronoff 2017, 2019) which argues that the coexistence of competing morphological schemas can be explained by their specialization in different areas of the lexicon (niches) even though they share the same function overall. Therefore, productivity might be local (e.g. specific to a certain domain) instead of global, and the identification of constraints on multiple levels and at different scales could help determine the selection of a schema for a specific base.

Whereas most work has focused on the identification of semantic and argument preferences, the present contribution, tied in with these recent developments, aims to investigate the potential morphological constraints that might play a role in the competition between -age, -ment and -ion suffixations. Lapraye (2017) has already identified preferences for verbs of the first group for -age and verbs of the second and third group for -ment, but the construction of the verbal bases that these three schemas select has never been studied so far. As a first attempt to pave the way for large scale analyses of the phenomena, our pilot study aims to search for morphological constraints by looking at the preferences that the schemas have for denominal or deadjectival verbal bases which constitute a significant proportion of the constructed bases that the schemas select –although deverbal verbal bases can also be selected by these schemas. Following on from this, several questions are tackled : do the schemas occupy different morphological niches ? Are some schemas more specialized than others ? If so, could the salience of these morphological niches be linked to the productivity of these schemas ? First, we provide quantitative evidence for the productivity of -age, -ment and -ion (Section 2). Using data collected from massive web corpora, we show that the schemas occupy morphological niches that rarely overlap when selecting verbs derived from nominal or adjectival bases (Section 3) and that the degree of specialization correlates with the degree of global productivity.

2. Assessing the productivity of deverbal nominalization schemas

As far as we know, the productivity scores of the suffixes that construct event nouns in French have not been compared quantitatively. Although Dal et al. (2008) compared the productivity of -ion with other suffixes such as -able, -ifier, -ique, -if and -eux using Baayen’s measures of productivity (1992, 1994), the productivity of competing suffixes in the construction of event nouns has not been examined. So far, the high predictability of the semantic interpretation of -age, -ment and -ion’s derivatives (henceforth Nage, Nion and Nment) led to considering these schemas as the most productive in that regard (Fradin 2014), but the lack of massive empirical data has made it difficult to prove this assumption and rank the three suffixes exhaustively. To provide quantitative evidence for the productivity of these schemas, we used an existing lexical database, VerNom (Missud, Amsili & Villoing 2020) and tested several productivity measures.

2.1. Extraction of V → N pairs

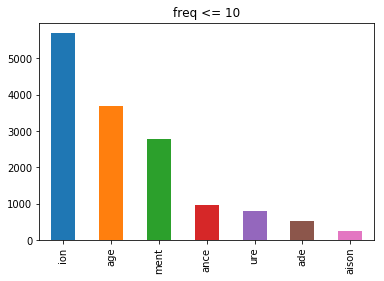

VerNom is a lexical database consisting of 25 857 verb-noun pairs acquired automatically from frCOW (Schäfer & Bildhauer 2012 ; Schäfer 2015), a massive French corpus from the web consisting of 9 billion words. In VerNom, the frequency of occurrence in frCOW of each verb and noun is documented. The database covers the main suffixations that construct event nouns in French. The average accuracy score of the morphological pairs reaches 87 %. The proportion of pairs per suffix is detailed in Table 1 in descending order. A visualization of the hierarchy is given in Figure 1. We extracted all the pairs in order to measure the productivity of the schemas.

|

Number of pairs |

Proportion |

|

|

-ion |

10558 |

40.8% |

|

-age |

6588 |

25.4% |

|

-ment |

4865 |

18.8% |

|

-ance |

1439 |

5.5% |

|

-ure |

1252 |

4.8% |

|

-ade |

771 |

2.9% |

|

-aison |

384 |

1.4% |

|

Total |

25857 |

100% |

Table 1. Proportions of pairs per nominalization schema.

Figure 1. Rank of the nominalization schemas according to the proportions of pairs.

2.2. Productivity measures

Considering the lack of consensus on productivity measures, we measured the productivity of the suffixes in our database in two different ways. For the application of each of the following measures, variants of the same suffix for a unique verbal base such as annihilation / annihilition ‘annihilation’ were ignored.

First, we used (Baayen 1994)'s formula to calculate the hapax-conditioned degree of productivity. Based on the idea that neologisms are prone to appear among the least frequent words (especially words with a frequency of 1), the formula gives a probability of finding hapax legomena ending with a specific suffix among all the hapax legomena in the data. Examples of hapax legomena for each suffixation are given in (2). However, as many neologisms were found among more frequent nouns (with a frequency of 10 for example), we also tested different frequency ranges. In order to provide an intuitive visualization of the productivity of the schemas, figures 2 and 3 present the proportion of hapax legomena (Figure 2) and nouns that have 10 or fewer occurrences (Figure 3) according to the schema they derive from. In each case, the distribution remains identical.

|

(2) |

-ion : |

acadianisation ‘acadianizing’, évangélicalisation ‘evangelization’, étouffation ‘choking’ |

|

-age : |

évanouissage ‘fainting’, acceptationnage ‘acceptance’, épilogage ‘making a fuss’ |

|

|

-ment : |

émancipement ‘emancipation’, œuvrement ‘execution’, éperonnement ‘ramming’ |

|

|

-ance : |

zyeutance ‘stare’, époustouflance ‘mind blow’, éveillance ‘awakening’ |

|

|

-ure : |

argumentature ‘argumentation’, bricolure ‘DIY’, étoilure ‘starrying’ |

|

|

-ade : |

écœurade ‘sickness’, trottinade ‘scampering’, vociférade ‘yelling’ |

|

|

-aison : |

séparaison ‘separation’, trouvaison ‘finding’, vilipendaison ‘vilifying’ |

Figure 2. Productivity scores of each nominalization schema (hapax legomena).

Figure 3. Productivity scores of each nominalization schema (derived nouns with 10 or fewer occurrences).

However, the hierarchy differs when only the most frequent nouns are taken into account (Figure 4). Examples for the most frequent deverbal nouns are given in (3).

|

(3) |

-ion : |

information ‘information’, association ‘association’, application ‘application’ |

|

-age : |

usage ‘usage’, dépannage ‘troubleshooting’, apprentissage ‘learning’ |

|

|

-ment : |

développement ‘development’, gouvernement ‘government’, établissement ‘establishment’ |

|

|

-ance : |

connaissance ‘knowledge’, assurance ‘assurance’, croissance ‘growth’ |

|

|

-ure : |

procédure ‘procedure’, ouverture ‘opening’, écriture ‘writing’ |

|

|

-ade : |

promenade ‘promenade’, baignade ‘bathing’, bousculade ‘scramble’ |

|

|

-aison : |

comparaison ‘comparison’, conjugaison ‘conjugation’, déclinaison ‘declination’ |

Figure 4. Productivity scores for each nominalization schema

(high-frequency derived nouns with more than 1000 occurrences).

As shown in Figure 4, among the derived nouns with at least 1 000 occurrences, -ment is more productive than -age while -ion remains the most productive. Therefore, -ion is not only the most productive among the least frequent pairs, but it also counts the largest number of pairs among the most frequent pairs in our data. The higher rank of -ment could be due to -ment’s earlier attestation in French (Uth, 2012), which potentially implies that -ment nominalizations might be more lexicalized than -age derived nouns on average.

Apart from Baayen’s measure, we used (Yang 2016)’s Tolerance Principle. By presupposing that productive rules are necessarily applicable to a sufficiently large number of items, this measure gives a productivity threshold for every suffix by dividing the total number of items (in our case, all the suffixed nouns we collected) by its natural logarithm. Applied to our data, the measure gave a threshold of 2 478. Suffixes that have a total number of suffixed items that is higher than the threshold are considered productive. As shown in Table 2 (see following page), only 3 suffixes exceeded that threshold : -ion, -age and ‑ment.

Both measures show that -ion, -age and -ment clearly stand out from -ance, -ure, -ade and -aison suffixations. -ion suffixation is by far the most productive in our data, and -ment suffixation is the least productive among the three most productive ones. A natural assumption based on these productivity scores would be that -ion might have a larger choice of verbal bases at its disposal than its counterparts. However, local productivity could play a role in keeping -age and -ment productive as well. While this section provided some insight into the schemas’ global productivity, the following section focuses on local productivity accounts on the morphological level.

|

Number of pairs |

|

|

-ion |

10141 |

|

-age |

6489 |

|

-ment |

4672 |

|

Threshold |

2478 |

|

-ance |

1430 |

|

-ure |

1228 |

|

-ade |

769 |

|

-aison |

379 |

Table 2. Number of pairs without variants including Yang’s tolerance principle threshold.

3. Morphological properties of verbal bases

While the morphological complexity of the base nouns of French denominal adjectives in -aire, -al, ‑el, -esque, -eux, -ien, -ier, -u or -ique has been quantitatively studied (Strnadová, 2014), our study aims to capture -ion, -age and -ment suffixations’ preferred verbalization schemas. In order to shed light on the constraints that might emerge on the morphological level, we examined the morphological structure of the verbal bases that -ion, -age and -ment select among the pairs of our data. Because of the noisy nature of the data collected from frCOW and the need to clean the data manually, this study is limited to denominal and deadjectival verbal bases only, excluding deverbal verbal bases, whether prefixations (dé-, re-, sur-, sous-, pré- ; cf. examples in (4)) or evaluative suffixation (-ailler, ‑asser, ‑onner, -eter, -eler, -iner ; cf. examples in (5)).

|

(4) |

a. |

coloniser ‘to colonize’ → décoloniser ‘to decolonize’ → décolonisation ‘decolonization’ |

|

b. |

ajuster ‘to adjust’ → réajuster ‘to readjust’ → réajustement ‘readjustment’ |

|

|

c. |

classer ‘to grade’ → surclasser ‘to upgrade/ to outclas’ → surclassement ‘upgrading’ |

|

|

d. |

alimenter ‘to feed’ → sous-alimenter ‘to undernourish’ → sous-alimentation ‘undernourishment’ |

|

|

e. |

chauffer ‘to heat’ → préchauffer ‘to preheat’ → préchauffage ‘preheating’ |

|

|

(5) |

a. |

traîner ‘to hang around’ → traînailler ‘to hang around’ → traînaillement ‘hanging around’ |

|

b. |

rêver ‘to dream’ → rêvasser ‘to daydream’ → rêvassement ‘daydreaming’ |

|

|

c. |

chanter ‘to sing’ → chantonner ‘to hum’ → chantonnement ‘humming’ |

|

|

d. |

voler ‘to fly’ → voleter ‘to flit around’ → voletage ‘flittering around’ |

|

|

e. |

craquer ‘to split’ → craqueler ‘to crackle’ → craquelage ‘crack’, ‘cracking’ |

|

|

f. |

trotter ‘to trot’ → trottiner ‘to jog’ → trottinement ‘jogging’ |

To assess the proportion of verbs derived from nouns or adjectives and other types of bases (‘simple’ or deverbal bases), we identified constructed verbal bases by finding their corresponding nominal or adjectival base in frCOW. We targeted the most representative verbalization schemas in that regard : ‑iser and -ifier suffixations, noun or adjective to verb conversion, and a-, en-, é- and dé- prefixations. -oyer suffixation (guerre → guerroyer ‘make war’) for which too few data were found was ignored.

Table 3. Examples of N/A → V → Nion / Nage / Nment triplets. 2

For the purpose of finding N/A → V → N triplets, we proceeded automatically by truncating the infinitive marking from the prefixed and suffixed verbs that are linked to a Nion, Nage or Nment in VerNom. The truncated forms were then matched against all forms that are tagged nouns and adjectives in frCOW using Levenshtein's edit distance : if a noun or an adjective was strictly identical to a truncated verb, or if a distance of 1 character only (last character of the forms) separated them, a triplet consisting of the base of the verb, the verb itself and the deverbal noun in -ion, -age or -ment was collected along with the frequency of each lexeme in frCOW.

As conversion does not display formal regularities, allomorphy for converted nouns and verbs was considered using Levenshtein’s edit distance on the last two characters of the candidate forms. The resulting triplets that were automatically extracted were then verified manually. The directionality of conversion (verb to noun / adjective or noun / adjective to verb) was not taken into account (e.g. Tribout 2010) as we kept any verb that could be morphologically related to a noun or an adjective (oubli ‘oversight’ – oublier ‘to forget’). Under the same perspective, we decided to keep the ambiguous dé- prefixed verbs that could be constructed either on a noun or a verb (bruit ‘noise' → bruiter ‘to add noise' → débruiter ‘to remove noise'), as long as a noun could be identified. A total of 2 669 triplets (paired with the frequency of each lexeme in frCOW) were found. As an indicator, deverbal verbs in dé- (for which no morphologically related noun could be found), re-, sur-, sous-, pré- and -ailler, ‑asser, -onner, -eter, -eler, -iner (as in (4) and (5)) were extracted and paired with their verbal bases automatically as well (although not filtered manually unlike denominal or deadjectival verbs) in order to have some idea of the proportion of constructed versus simple bases that -ion, -age and -ment suffixations select. The number of verbs collected per verbalization schema is listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Number of verbs per verbalization schema.

3.1. Denominal & deadjectival, deverbal and simple(x) bases

The proportions of denominal and deadjectival verbs, deverbal verbs and other kinds of bases (where we expect to find a significant proportion of simple verbs) selected by each nominalization schema are given in Table 5. The percentages are calculated by row and the values in bold represent the highest proportion for a column. In each case, the proportions show that the three schemas preferentially select non-denominal and non-deadjectival bases (i.e. what we have called ‘other’3, such as simple verbal bases like gérer ‘to manage’ → gestion ‘management’ or gonfler ‘to inflate’ → gonflement ‘swelling’ as well as compounds like écoinnover ‘to ecoinnovate’ → écoinnovation ‘ecoinnovation’), but that they also select constructed verbal bases in different proportions. Denominal and deadjectival verbs are mostly found in triplets involving a ‑ion derivative (15 %), whereas deverbal verbs are slightly more represented among -age (11 %) than -ion (10.7 %) and -ment triplets (10.8 %). Triplets involving a -ment derivative contain the highest proportion of verbs that are not derived from a nominal, adjectival or verbal base (80.1 %). Note that the proportions for deverbal verbs are indicative as they were not corrected and that the difficulty of finding and pairing converted nouns and verbs automatically might diminish the actual proportion of constructed verbs.

Table 5. Proportions of verbs according to their construction among -ion, -age and -ment verbal bases.

Additionally, we looked at the proportions among derived nouns with 10 or fewer occurrences, hoping that this would help capture neologisms and give an indication of the current preferences of the schemas4. The proportions for low frequency nouns given in Table 6 remain quite similar with a frequency threshold. Among the triplets containing the least frequent derived nouns, -ion is still the suffix that favors denominal and deadjectival constructed verbs the most. The proportion is slightly higher than in the general case (18.4 %). On the other hand, -age and -ment take a greater portion of derived verbs, with -ment selecting a higher proportion of deverbal verbs (13.7 %) than -age (13.3 %), even though both still seem to select few constructed verbs to derive potential neologisms compared to -ion.

Table 6. Proportions of verbs according to their construction among -ion, -age and -ment verbal bases (Nage, Nion and Nment of 10 or fewer occurrences).

3.2. Morphological preferences for the nominalization schemas

3.2.1. The morphological schemas behind denominal and deadjectival constructed verbs

As regards the schemas at the origin of the construction of verbs that the three nominalization suffixes select, preferences are very distinct. The number of denominal and deadjectival constructed verbs per schema is shown in Table 7. Values in bold represent the highest number for a column. Some examples of constructed verbs with high and low frequency are given in (6) : verbs suffixed in -iser (6a) and ‑ifier (6b), verbs converted from a noun or an adjective (6c) ; verbs derived from a- (6d), en- (6e) é- (6f) and dé- prefixations (6g).

Table 7. Number of triplets according to their construction for each nominalization schema.

|

(6) |

a. |

créole ‘Creole’ → créoliser ‘to creolize’ → créolisation ‘creolization’ |

|

b. |

complexe ‘complex’ → complexifier ‘to make more complex’ → complexification ‘complexification’ |

|

|

c. |

vaccin ‘vaccine’ → vacciner ‘to vaccinate’ → vaccination ‘vaccination’ |

|

|

d. |

coquin ‘little rascal’ → acoquiner ‘to team up with’ → acoquinage ‘collusion’ |

|

|

e. |

tour ‘turn’ → entourer ‘to surround’ → entourage ‘entourage’ |

|

|

f. |

goutte ‘drop’ → égoutter ‘to dry’ → égouttage ‘draining’ |

|

|

g. |

nerf ‘nerve’ → dénerver ‘to remove the nerves from [sth]’ → dénervage ‘nerve removal’ |

|

The proportions are calculated by row in Table 8 and by column in Table 9 and give two different interpretations. In Table 8, we measure the proportion of denominal or deadjectival bases selected by each schema (i.e., how many verbs in -iser are selected by -ion among all the denominal or deadjectival verbs that -ion selects). These proportions express the schemas’ preferences by highlighting the type of bases they mostly use. The values in bold correspond to the highest percentage for a schema.

Table 8. Proportion of triplets according to their construction for each nominalization schema.

On the other hand, in Table 9 we divide the number of a certain type of denominal and deadjectival bases selected by a schema by the total number of the type of base. For example, 95.6 % of -iser verbs are selected by -ion since 1218 -iser verbs of our data out of 1274 (as shown in Table 7) are the bases of a -ion derivative. These proportions give an indication of how exclusive a type of base is to a specific schema.

Table 9. Proportions of verbs selected by the nominalization schema according to their type.

The results in Table 8 show that the three suffixes have definite preferences for certain kinds of constructed verbs. -ion suffixation strongly favors -iser suffixed verbs (77.6 %) while also selecting a portion of -ifier (10.8 %) and converted verbs (7.3 %). It only marginally selects prefixed verbs ; at best, 1.7 % Nion are derived from dé- verbal bases. Although -age suffixation's preferences are less concentrated, 45.6 % of Nage are constructed on converted verbs. An important proportion of dé- (21.1 %) and en- (16 %) verbal bases can also be found selected by -age suffixation while the proportions of ‑iser (5.9 %), -ifier (1 %) and a- prefixed verbs (2 %) are far behind. In comparison, -ment suffixation seems more versatile : it mostly selects en- prefixed verbs (36 %) but a similar proportion of converted verbs is also selected (34.1 %). The proportions show that -ment favors other prefixed verbs apart from en- verbs (10.4 % of a-, 8.1 % of dé- and 6.9 % of é- verbs) more than suffixed verbs (3.7 % of -iser and 0.1 % of -ifier verbs).

As shown in Table 9, some bases are almost exclusive to certain types of nominalization schemas. Notably, an overwhelming majority of -iser (95.6 %) and -ifier verbs (95.5 %) are selected by -ion suffixation. On the other hand, conversion is used as a Nage base in most cases (53.7 %), but when it is not, it can also be selected by -ment (25.8 %) and by -ion (20.3 %). Prefixed verbs in a- and dé- are more exclusively selected by -age and -ment in this regard : 68.1 % of a- bases derive -ment derivatives, while 69.6 % of dé- bases are selected by -age. As converted bases, about half of en- and é- bases are selected by one schema : en- bases are mostly selected by -ment (55.5 %) and é- by -age (55.1 %). A significant proportion of Nage are derived from an en- base (38.7 %), while the same applies for -ment with é- (30.6 %).

The proportions that are highlighted in Tables 8 and 9 can be combined in order to reflect the schemas' preferences and accessibility to certain types of bases. As -iser is strongly preferred and almost exclusively selected by -ion, the niche effect is amplified. The same applies for -age with converted verbs and for -ment with en- verbs although to a lesser extent since the proportions are not as striking.

The niches that the three suffixes occupy do not have the same degree of salience as -ion seems more specialized than -age and -age more specialized than -ment. Such gradable preferences seem to correlate with the productivity rank of the nominalization schemas (-ion > -age > -ment). In this regard, a distinction can be made between a morphological schema’s global productivity, i.e. its ability to be used in general without considering the features of the bases that are selected (as investigated in Section 2), and its local productivity that is limited to the selection of a specific type of base. In our case, we specifically define local productivity as the manifestation of the preferred type of base of a suffix, regardless of its overall productivity in the general case. Global and local productivity are not necessarily negatively or positively correlated : a suffix can have a lower global productivity compared to its rivals and still be predominant in selecting a specific type of base, or it can be the most globally productive while remaining versatile in its choices of bases. To assess the local productivity of the three suffixes regarding base selection, neologisms are needed to investigate whether some verbal bases are more exclusively selected by certain schemas. As for global productivity, we focus on derived nouns with 10 or fewer occurrences as a way to detect potential neologisms that are more prone to appear among low-frequency lexemes (Baayen, 1994). We sampled the triplets and looked at the same proportions among the triplets that contain the least frequent event nouns (10 occurrences or less). A total of 1524 low-frequency triplets were found. The number of triplets per nominalization and verbalization schema is given in Table 10. The proportions of suffixed nouns per verbalization schema are detailed in Table 11 (by row), and the proportions of verbal bases according to their schemas per nominalization schema in Table 12 (by column).

Table 10. Number of triplets according to their construction for each nominalization schema (derived nouns with 10 or fewer occurrences).

Table 11. Proportion of triplets according to their construction for each nominalization schema (derived nouns with 10 or fewer occurrences)

Table 12 ( =Table 9 supra). Proportions of verbs selected by the nominalization schema according to their type (derived nouns with 10 or fewer occurrences).

While the preferences remain the same overall, they are sometimes enhanced when looking at the triplets that have the least frequent derived nouns. -ion favors -iser even more (79.2 % ; see Table 11) ; however, the higher amount of converted verbs among the low-frequency triplets gives a slightly more balanced preference for -ifier suffixed verbs (9.5 %) and converted verbs (7.7 %). Still, -iser and -ifier verbs are almost exclusively selected by -ion (94.5 % for -iser, 93.6 % for -ifier ; see Table 12). Although conversion remains -age’s preferred verbalization schema (39 % of its bases and 44.9 % of all converted bases ; see Table 11), -ment now mostly selects converted verbs (40 %), even though it still counts the highest proportion of a- and en- prefixed verbs (see Table 11). Both -age and -ment select é- prefixed verbs in almost the same proportions (5.4 % of -ment and 5.1 % of age’s bases in Table 11). Examples of triplets according to their frequency are given in (7).

|

(7) |

a. |

N > -iser suffixation > Nion |

|

b. |

N > -ifier suffixation > Nion |

|

|

c. |

N > conversion > Nage |

|

|

d. |

N > en- prefixation > Nment |

|

|

e. |

N > conversion > Nment |

|

The closeness of -age and -ment can be explained by the fact that they often select the same verbal bases : 35 -age /-ment doublets were found among the least frequent derived nouns and these are mostly constructed on converted verbs (20/35) (see (8a)) and en- prefixed verbs (12/35) (see (8b)). 13 ‑ion /‑ment doublets were collected as well, and exclusively concern converted verbs, (see (8c)) while only 3 ‑age /‑ion doublets involving converted nouns were found (see (8d)). For most doublets involving -ment, the -ment suffixed noun is generally less frequent than the other suffixed noun. The lack of overlapping base verbs between -age and -ion as well as the number of doublets that involve -ment could indicate a lack of specialization in selecting converted verbs for -ment compared to the other two suffixations.

|

(8) |

a. |

age / -ment doublets on converted verbs (low-frequency) |

|

b. |

age / -ment doublets on en- prefixed verbs (low-frequency) |

|

|

c. |

-ion / -ment doublets on converted verbs (low-frequency) |

|

|

d. |

-age / -ion doublets on converted verbs (low-frequency) |

|

To summarize, a niche effect was found in the selection of verbal bases depending on their construction : -ion has the highest proportion of nouns derived from denominal and deadjectival constructed verbal bases and strongly favors -iser and -ifier verbalizations, -age is the most inclined to select converted verbs, and -ment favors denominal and deadjectival prefixed verbs. The salience of these niches differs from one nominalization schema to another and follows approximately the same hierarchy as that of the global productivity scores. -ion is the least versatile of all, -age distributes its preferences among converted verbs (mainly), dé-, en- and é- prefixed verbs as well as -iser bases as a minority, and -ment is the most versatile.

3.2.2. -ion versus -isation

Considering the predominance of -isation (and to a lesser extent, -ification) nouns, one could argue that -isation might have become a suffix on its own (or is slowly becoming one) (as proposed by Lignon et al. 2014 and Dal & Namer 2015 based on less data from frWaC (Baroni et al. 2009)) or that -ion's productivity could almost exclusively depend on the existence of -iser or -ifier verbs (Lignon et al. 2014), given that -ion productivity in general is low (as shown by Dal et al. 2008, based on data from the newspaper Le Monde). However, the proportion of -isation and -ification nouns compared to other -ion nouns in our data presented in Table 13 shows that the majority of -ion nouns are not constructed on -iser or -ifier verbs, even among the least frequent nouns where we expect to find neologisms (10 or fewer occurrences). Only 32.4 % of -ion derived nouns in VerNom are constructed on -iser verbs in the general case, while 4.7 % are constructed on -ifier verbs. The remaining 62.8 % correspond to other kinds of verbs that -ion selects (non-denominal, non-deadjectival and non-deverbal). These proportions remain stable when looking at the least frequent derived nouns (frequency < 10) : 62.6 % of -ion nouns are not derived from an -iser or -ifier verbal base (see examples (9a)), 32.3 % are derived from -iser (see examples of -iser verbs in (9b)) and 4.9 % from -ifier verbs (see examples in (9c)). Although the proportion of -isation nouns is strikingly significant, -ion’s preference for -iser verbs does not increase when looking at potential neologisms.

Table 13. Proportion of -ion, -isation and -ification nouns in VerNom.

|

(9) |

a. |

accabler ‘overburden’ → accablation ‘denunciation’ ; problémer ‘to make an issue’ → problémation ‘making an issue’ ; gloubiboulguer ‘to cook the ‘gloubiboulga’ imaginary dish’→ gloubiboulgation ‘cooking the ‘gloubiboulga’ imaginary dish’ ; inimaginer ‘to unbelieve’→ inimagination ‘lack of imagination’ ; périmer ‘to expire’ → périmation ‘expiration’ ; morceler ‘divide’ → morcellation ‘dividing up’ |

|

b. |

rivaliser ‘to compete’ → rivalisation ‘rivalry’ ; tyranniser ‘'to tyrannize’→ tyrannisation ‘tyranny’ ; agoniser ‘be dying’ → agonisation ‘death throes’ ; expertiser ‘to assess’ → expertisation ‘expert assessment’ ; portraitiser ‘to portraitize’ → portraitisation ‘portraitization’ |

|

|

c. |

syllabifier ‘to syllabify’ → syllabification ‘syllabification’ ; sous-qualifier ‘to underqualify’ → sous-qualification ‘underqualification’ ; reclarifier ‘to clarify again’ → reclarification ‘clarification again’ ; obésifier ‘to obesify’ → obésification ‘getting obese’ ; webifier ‘to webify’→ webification ‘webification’ ; scorifier ‘to scorify’ → scorification ‘scorifying’ |

However, we are able to confirm Kerleroux's hypothesis (2008) that -ion’s productivity is mostly founded on -ation forms : these forms account for 79.8 % of -ion derived nouns in general, and 79.6 % of the derived nouns in -ion that have a frequency of 10 or less in frCOW, as shown in Table 14. The productivity of -ion includes -isation and -ification nouns, but not as a majority since most -ation nouns are not derived from an -iser or -ifier verbal base (55 % among the least frequent nouns, 55.2 % in general as shown in Table 15). Therefore, it is likely that -ion's preference for -iser and -ifier verbs depends on -ion’s preference for -at- stems. Further work is necessary to verify this hypothesis.

Table 14. Proportion of -ion, -ation and -ion without -ation in VerNom.

Table 15. Proportion of -ation, -isation, -ification and -ation without an -iser / -ifier base.

4. Conclusion

This study has highlighted some of the morphological constraints that might play a role in the competition between -ion, -age and -ment deverbal suffixations in terms of base selection. We showed that although all three schemas mostly select non-denominal, non-deadjectival and non-deverbal verbal bases, -ion is by far the one that selects denominal and deadjectival verbs the most. By examining these constraints, we found that the three nominalization schemas occupy different morphological niches : -ion strongly favors -iser and -ifier suffixed verbal bases, -age mostly selects converted verbs and dé- prefixed verbs while sometimes choosing é- and en- prefixed bases, whereas -ment specializes in the selection of a- and en- prefixed verbs, but its preferences are distributed more evenly than the other two schemas. The salience of the niches seems to correlate with the global productivity scores that we calculated for the three schemas : -ion, the most productive of all the suffixations that construct event nouns in our data, is also the one that has the most pronounced preferences. Conversely, -ment suffixation is the least productive among the three schemas and it is also the most versatile in its selection of verbal bases. -age suffixation, the second most productive of the three, shows stronger preferences than -ment, but not as definite as those of -ion suffixation. As a significant proportion of bases derived from verbs has also been found, further work on the type of deverbal bases (dé-, re-, sous-, sur-, pré-, ailler-, -inner, -onner, -eter, -eler...) that the three nominalizating suffixes select is the next step as it might give more complete insight into the schemas' preferences on the morphological level.

Of course, this study only investigated one of the many features that might explain the coexistence of the suffixations that construct event nouns in French. However, in the case of morphological competition, one can hypothesize that it is advantageous for rival schemas to occupy salient morphological niches, but that the choice of the niches is risky depending on the productivity of the schemas involved (notably, a- prefixation that is favored by -ment concerns fewer constructed verbs than -iser or conversion ; hence the productivity of -ment might be impacted by the lack of productivity of a- prefixation). On the other hand, versatility, as observed in the case of -ment, might lead to a more stable productivity overall, but might also be partly responsible for a decline in productivity for the suffix whenever its competitors have taken beneficial risks (for example : converted verbs for -age that -ment selects as well although not to the same degree, making -ment disadvantaged compared to -age when selecting converted verbs). In the context of denominal and deadjectival base selection, we showed that the phenomenon is gradable as -ion, -age and -ment are all globally productive and all have distinct preferences that make them seem specialized although not to the same degree. In the light of Lindsay and Aronoff's work on morphological rivalry (2013), as well as the theory developed further by Aronoff (2016, 2017, 2019), our results could provide evidence that local productivity and niche occupation might actually favor competing schemas. Modelling the salience of the niches in order to score the niche effect that we observed in each situation (-ion with -iser, -age with conversion, etc.) is a crucial next step to investigating the local and global productivity dynamics that allow the suffixes to coexist. Further work on the relation between niche salience and global productivity needs to be conducted quantitatively on a larger scale by taking semantic, paradigmatic and phonological niches into account in order for this hypothesis to be formulated.