Introduction

Female portrait statuary forms a large and important category of evidence for understanding the historical phenomenon of the visual representation and commemoration of women in the public and sacred spaces of the Greek city. With its rich body of both epigraphical and sculptural remains, the city of Athens is a particularly fruitful site to undertake such a study. While portraits of women begin to be set up in Athens in the early fourth century B.C., the chronological focus here is the first three centuries A.D., when inscribed bases for statues of women and marble sculpture representing female portrait subjects are at their most abundant. I consider bases that held statues of women from the following locations: the Acropolis, the City Eleusinion, the Sanctuary of the Two Goddesses at Eleusis, and the Athenian Agora. These sites were chosen because the inscriptions from each have been well published and well-studied. The main sculptural evidence comes from the American excavations in the Athenian Agora. As the largest body of sculptural evidence from a single excavation area in the city, the Agora material is crucial for understanding the history of Athenian portraiture in the Roman period.1

Although a great deal of important research has focused on the epigraphic evidence for votive and honorific portrait statues, particularly from the Acropolis and the Agora, I focus here exclusively on statues of women and attempt to analyze and to put into conversation both strands (the epigraphic and the sculptural) of this material. While these two strands of evidence do not in any case overlap—that is, we cannot associate any of the preserved portraits to a particular inscribed base—the underlying assumption is that the women represented in the marble statuary are the same kinds of elite female subjects honored in the inscribed bases, which is an hypothesis that guided our interpretations of the portrait statuary from Aphrodisias.2 I limit my analysis to the statues of local, that is non-imperial, subjects, which in any case comprise most of the available epigraphic and sculptural evidence. As I have argued elsewhere, in comparison to the statues of local honorands, statues of the imperial family were in the minority in the sculpture landscape of Roman Athens, and these Imperial images also had different purposes and meanings.3 My aim is to explore the range of local women represented by the inscribed statue bases, who set up these statues, when, and why, and how these women may have been represented visually in their portraits. I begin with the epigraphic evidence and then turn to the portrait sculpture from the Agora.

The epigraphic evidence for female portrait statues

The epigraphic evidence from Athens for portrait statues of women consists almost entirely of inscribed statue bases. Inscribed decrees documenting the official decision by a corporate group to award a portrait statue to a particular individual was almost always confined, not surprisingly, to male honorands.4 There are, however, vanishingly few such decrees even for male honorific statues in the Imperial period: almost all of the preserved statue decrees are Hellenistic in date.5 There are a few bases which show that statues of women were sometimes publicly sanctioned by the demos or other corporate groups, although the overwhelming majority of female portrait statues in both the Hellenistic and Roman periods were set up by family members. On the other hand, it is important to remember that while the distinction we make between publicly sanctioned honorific portrait statues and privately dedicated ones does reflect a real difference in the mechanisms by which these statues were set up and who might have financed them, both categories of portrait were visible within the public spaces of the city. In fact, public honorific and privately dedicated portraits were sometimes part of a single statue monument.6 And while the financing of honorific portraits bestowed by the demos or other corporate groups most likely came from public funds, even publicly decreed statues might sometimes have been paid for, albeit perhaps partially, with private funds.7

I survey the evidence for the inscribed bases for portrait statues of women by their display location. I have limited my sample to those bases that either preserve the name (or indication of the gender) of the honorand or the role for which they were being honored. I have also tried to include only those bases that are more likely than not to have originally been set up at the site where they were found. It is well known, for example, that some of the inscribed bases currently on the Acropolis were moved there during the 19th century from elsewhere in the city for safekeeping,8 and that a great deal of ancient material of all kinds migrated into the Athenian Agora in the post-Antique period for use as building material.9 So while the bases I have grouped under the heading “Acropolis” perhaps were set up elsewhere, I have tried to mitigate this problem in the case of the Agora by including only those bases that come from authentically ancient contexts. Finally, for most of the sites I focus on a few representative examples to sketch out the broader patterns of portrait practice over time. A more complete list of the inscribed bases is included in an appendix.

The Acropolis

The earliest preserved base from Athens for the bronze portrait statue of a woman comes from the Acropolis: Lysimache priestess of Athena Polias.10 But it was not until the second half of the third century B.C. that statues of local women and girls begin to be set up in significant numbers on the Acropolis, leading Ralf von den Hoff to characterize the Hellenistic Acropolis as “an especially female space.”11 These Hellenistic-period statues represented young minor cult officials, such as ἀρρηφόροι (carriers of sacred things) and κανηφόροι (baιsket bearers), set up primarily by the young girls’ fathers,12 and priestesses, mainly of Athena Polias, dedicated mostly on the initiative of the women’s families.13 In contrast to the Hellenistic period, the Imperial-period Acropolis can no longer be characterized as “an especially female space,” as portrait statues representing a wide range of individuals, both local and foreign and mostly male, begin to crowd the sanctuary, underscoring its long-established Panhellenic character and prestige.14

Statues of ἀρρηφόροι continue to be dedicated on the Acropolis, and are particularly numerous in the Augustan period and the first century A.D.15 While most were set up by the girl’s parents, two early Imperial-period statues of these minor cult officials were authorized by the boule and the demos: one for Apollodora daughter of Apollodoros,16 and the other for Tertia daughter of Lucius, who also served as κανηφόρος of the Eleusinian and as hearth-initiate of the Mysteries.17 Apollodora’s base shows that the statue was set on column, as we know that some of the Archaic korai statues also were, and that it was made of bronze, as was the statue of Tertia. Also from the early Imperial period is the bronze statue of Stratokleia, priestess of Athena Polias, set up by her parents.18 Perhaps the concentration of such statue monuments during the early Imperial period had something to do with the renewed emphasis on religious piety, manifested in the renovations of religious structures in Athens under Augustus, including the Erechtheion,19 in the vicinity of which the statues of the ἀρρηφόροι and the priestesses of Athena Polias are thought to have stood.20 Statues of female cult officials continue to be set up on the Acropolis into the 2nd century A.D., but at a much reduced rate. As we shall see, by this time much of the dedicatory activity, particularly for the commemoration of women, seems to have migrated to the Sanctuary of the Two Goddesses at Eleusis.

The City Eleusinion

The City Eleusinion, the urban sanctuary site for the celebration of the Eleusinian Mysteries, is located on the north slope of the Acropolis, along the Panathenaic Way about halfway between the Agora and the Acropolis.21 The history of the sanctuary extends from the Archaic period to late Antiquity, and this long period of mostly uninterrupted use demonstrates its fundamental importance to the religious life of ancient Athens. In addition to the Mysteries, the sanctuary also accommodated a number of other cults and religious celebrations; inscriptions mention a temple of Triptolemos, sanctuaries for Plouton and Asklepios, and facilities for the Thesmophoria. Most of the site the sanctuary occupied remains unexcavated, but the area that has been explored has produced a wealth of important finds.

According to Daniel Geagan’s analysis of the epigraphic evidence associated with the City Eleusinion, the majority of the preserved inscriptions belong to bases for statues, attesting to the elite status and wealth of the dedicators, as well as the prestige and importance of the sanctuary.22 The City Eleusinion is, in fact, a crucial context for the history of female votive portraiture in the city, particularly in its earliest stages in the fourth century B.C., when a series of female portrait statues made by the most famous Athenian sculptors of the day were set up in the sanctuary by family members.23 After a gap in the evidence for the third century, portraits of women begin to be set up again in the sanctuary in the second century B.C., and include priestesses of Demeter and Kore24 and young female cult functionaries such as παῖδες ἀφ᾽ ἑστίας (hearth-initiates) and κανηφόροι.25 As on the Acropolis, votive statue dedications continue into the Imperial period at the Eleusinion, but here also at a much reduced rate. We have only two inscribed statue bases from the early first century A.D., both exceedingly fragmentary: one for a hearth-initiate named Phileto, set up by her parents and dedicated to Demeter and Kore,26 and another for a girl named Sostrate, who had served as κανηφόρος, ζάκορος (temple-servant) and κλειδοῦχος (key-bearer) the monument set up during the archonship of Nikostratos.27

As I have already mentioned, based on the epigraphic evidence from Eleusis, it would appear that beginning in the first century B.C. most of the dedicatory activity had shifted from the City Eleusinion to the Sanctuary of the Two Goddesses.28 Perhaps the increased interest in Eleusis and the Mysteries by Romans beginning in the late Republican period,29 and then the close association in the 2nd c. A.D. of the sanctuary with the Panhellenion may account for this change in focus.30 Of course, the apparent drop off in dedications at the City Eleusinion may well be due not to an historical reality, but to the lack of archaeological excavation, as most of the urban sanctuary still lies beneath the modern city. In any case, the evidence we do have from the sanctuary diminishes significantly over the course of the Imperial period, with a large gap between the statues of two minor cult functionaries cited above to a single female portrait statue set up in the early third century A.D. for one Annia (Statilia?), wife of the sophist Valerius Apsines of Gadara and herself of renowned Kerykid ancestry.31 As a member of the illustrious Claudii of Melite and granddaughter of the altar priest Claudius Sospis, it is no surprise that the setting up of her statue was approved by decree of the Council of 500. According to the inscription, she seems not to have served any function in the Eleusinion cult but was rather honored for her distinguished familial connections.32

The Sanctuary of the Two Goddesses at Eleusis

According to Kevin Clinton’s catalogue of inscriptions from Eleusis, there were approximately 50 statues representing female subjects set up in the sanctuary of the Two Goddesses from the Augustan period to the late third century A.D.33 Portraits of young female cult functionaries, such as hearth-initiates and κανηφόροι, occur in large numbers.34 A few were sanctioned by the demos and the boule, but most of these statue monuments were set up by the girl’s parents and seemed to have clustered around the Telesterion. Women who served as priestess of Demeter and Kore and as ἱερόφαντις (high priestess of the Eleusinian cult) were also honored with portrait statues, again mostly set up by family members. The large number of portrait statues of women underscores the important role the sanctuary came to play in the Imperial period as a stage for elite Athenian families to perform their power and prestige.35

That female statues played a role in demonstrating a family’s social pre-eminence is shown by the statue of Claudia Philoxenia, ἱερόφαντις of Kore and daughter of Tiberius Claudius Patron of Melite.36 Her statue was set up by her sons, and the inscription also tells us that her father covered the altar of the Younger Goddess with silver, thus celebrating three generations of the family in a single monument. The statue is dated by the eponymous priestess Claudia Timothea, who served from ca. 90-105 A.D.37 Close family members also took the initiative in setting up the statues of priestesses of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis and use the opportunity to honor a whole range of mostly male relatives. For example, the very long inscription for the statue of Aelia Epilampsis comprises 30 lines and names her grandfather, uncle, cousins, son, and grandson, and the offices they held, such as archon, hoplite general, priest of Olympian Zeus, eponymous archon, and άγωνοθέτης (director of the games).38 Pomponius Hegias and his sister Pomponia Epilampsis, the grandchildren of Aelia Epilampsis, set up the statue at the end of the second century A.D. when he was archon. In honoring their grandmother as priestess of Demeter and Kore, they also insert themselves into this rich and distinguished family history.

Portrait statues of female hearth-initiates are by far the most numerous of the statues set up in Eleusis, accounting for about half of the inscribed statue bases for female subjects.39 These young cult personnel, comprising one girl and one boy, were initiated into the Mysteries at public expense, and served in this capacity for a year.40 Although the role of hearth-initiate in the Eleusinion cult has a long history, it wasn’t until the later second century B.C. that the practice of honoring hearth-initiates with portrait statues begins, an expansion in portrait honors that appears to have originated on the Acropolis with the statues of ἀρρηφόροι. Influential Athenian families took full advantage of this new opportunity to commemorate the cultic activities of their youngest members publicly and lavishly.

Because of the young age of the female hearth-initiates, most of the inscribed text on their statue bases is naturally given over to enumerating the offices and achievements of their male relatives. For example, of the 16 lines on the statue base for the bronze portrait of hearth-initiate Publia Aelia Herennia, the majority concern the many offices held by her father, Publius Aelius Apollonios, which included eponymous archon, king archon, and hoplite general.41 The inscription also tells us that the statue, which was dedicated by her mother, stood next to one of her great-uncle, who had served as δαδοῦχος (torchbearer), and that the family claimed descent from Konon and Kallimachos. As Clinton states, “The chief interest of this monument lies in what it tells us of the honorand’s relatives.”42 In addition, the arrangement of the inscription reveals the relative importance of the people named in the monument. In many inscriptions the names of the statue’s dedicators come first, with the name of the young hearth-initiate placed a few lines down from the top. For example, on the base for the statue of the hearth-initiate Claudia Alkia, the name of her father, Tiberius Claudius Hipparchos of Marathon, is prominently named in the first two lines, while her name occurs in the third.43 We see a similar arrangement on the statue base for the hearth-initiate Nummia Kleo, set up by her parents: their names take up the first 10 lines, with their daughter’s name at the very end of the inscription.44

Portrait heads of male hearth-initiates have been identified both in Athens and Eleusis based on their special iconography, which included a myrtle wreath and a “youth-lock”,45 but no female hearth-initiates have yet to be recognized among the preserved portrait sculpture from Athens. That these girls would also have worn some type of wreath is strongly suggested by the inscription on the statue base for a hearth-initiate named Praxagora, which tells us that she was crowned by a chorus of children at the ceremonies.46 Her bronze statue, which was set up by her parents Demostratos of Melite and Philiste in ca. 180-185 A.D., stood in front of the Telesterion, a prized location for the portrait of “a parents’ famous daughter,” which is what she is called in the inscription on the statue’s base.

The Athenian Agora

While the literary and epigraphic evidence show that the Agora was an overwhelming male dominated space in terms of the portrait statues set up there,47 a handful of inscribed statue bases for female portraits have been found in the excavations. Some of these bases, many of which are exceedingly fragmentary, were built into the post-Herulian Wall in the area of the Stoa of Attalos, a strong indication that rather than having been brought in from elsewhere in the city these monuments actually originally stood in the Agora.48 As the preeminent location for public honorific portrait statues, a statue in the Agora conferred a high degree of both prestige and visibility to the portrait subject. It is therefore not surprising that the women represented in these statues were all from super-elite Athenian families.

Four of the bases preserve the names of the women honored as well as the names of the dedicators of the statues. All date to the second century A.D. The portrait statue of Vibullia Alkia, wife of Tiberius Claudius Atticus and mother of Herodes Atticus, was set up by the tribe of Pandionis because of her ἀρετή (virtue) and εὐνοία (good will) towards the fatherland.49 This statue, which is Hadrianic in date, seems to have been part of a larger group of portrait monuments to her husband set up in the Agora around the same time by the various tribes in honor of their generous benefactions to the tribes when they held the prytany.50 That there were additional statues of Vibullia Alkia as well is shown by a prytany decree of the tribe of Aiantis, passed by the Council, that honors both her and her husband with gold crowns and statues.51

The boule of the Areopagus, the boule of the 600, and the demos honored Vitellia Isadora with a statue on account of her virtue.52 As the wife of Titus Flavius Alkibiades, she had married into the Flavii of Paiania, one of the four leading families of second-century Athens.53 Her husband held many important offices in the early second century, including eponymous archon, priest of Drusus, herald of the Areopagus, and hoplite general. In the later second century, her son, the hierophant Titus Flavius Leosthenes, was honored with a public honorific statue in the sanctuary at Eleusis for, among other things, initiating Lucius Verus into the Mysteries and presiding over the emperor’s adlection into the Eumolpidai.54 A portrait statue of her daughter, Flavia Phila, was set up in the Agora by Flavia’s husband in honor of her ἀρετή (virtue) and σωφροσύνη (moderation).55 Both statues were found rebuilt into the Church of Panagia Pyrgiotissa, at the SW corner of the Stoa of Attalos,56 and so probably stood in close proximity both to the Stoa and to each other. Like the other statues of women set up in the Agora, they are honored by virtue of their relationships to the illustrious and powerful men in their lives. Reflected glory perhaps, but glory nonetheless.

The fourth base, preserved in fragments that were found in or around the Stoa of Attalos, supported a portrait statue of Appia Annia Regilla, the wife of Herodes Atticus.57 The monument was set up by Flavius Sulpicianus Dorion, archon of the Panhellenion, “for the consolation of a friend.” Clearly this is a posthumous monument, set up after Regilla’s death. Although Geagan suggested that the statue probably stood in the City Eleusinion, as Herodes belonged to the genos of the Kerykes and his role as exegete is mentioned in the inscription, it seems just as possible that Regilla’s statue was set up on the public square in front of the Stoa of Attalos, as was Vitellia Isadora’s, who also had illustrious Eleusinian connections. The area in front of the Stoa of Attalos and the grand boulevard of the Panathenaic Way that passed in front of it became prime locations for portrait monuments in the later Hellenistic and Roman periods. As a major thoroughfare from one of the city’s main gates to the city center, it would have been in constant daily use. Such important and powerful Athenian families—members of three of Michael Woloch’s four leading families are represented in these statue monuments—could surely lobby for or even demand the most desirable location, the ἐπιφανέστατος τόπος (most prominent place) cited in many decrees, as the location and visibility of one’s portrait monument were always primary concerns.58 That portraits of women were clearly in the minority probably made these statues stand out even more within the predominantly male statue landscape of the Agora.

To briefly sum up some of the conclusions one can glean from these statue bases: the inscriptions for the statues of women and girls honor the religious activities of their subjects, but they are also concerned with commemorating the many high offices held by their male relatives, and by extension, the wealth and elite status of their families. When the women themselves are praised in these inscriptions for any personal qualities, it is their virtue and piety that are most frequently mentioned.59 Family traditions, political ambitions, and the preservation and commemoration of elite status all played a role in the decision to set up of these statues. Although these monuments represented a substantial financial investment,60 families seemed to have recognized that honoring their female family members for cultic service, even those that have served in minor roles, provided another opportunity to trumpet the broader accomplishments and euergestism of their male relatives, sometimes going back generations.

What might these female statues have looked like? While the inscribed bases provide information about the portrait subjects and the roles they and their families played in the political and religious life of Athens, the portrait statues that stood on these bases would have played an essential role in the visual impact of these monuments. In the few cases in which the crowning course is preserved, the bases suggest that most of the statues themselves were made of bronze. Unfortunately, none of these statues is preserved. The extant marble sculpture, however, provides important evidence for the visual appearance of these now missing bronze statues, as I would argue there is sufficient overlap between the preserved marble statuary, the figures on Attic tombstones,61 and preserved bronze statues from elsewhere to suggest they all participated in a shared visual language and expressed the same key ideas. The working hypothesis is that the individuals represented in the inscribed statue bases—wives, daughters, priestesses, minor cultic functionaries—are the same kinds of elite subjects represented in the marble statuary, to which I now turn.

The sculptural evidence for female portrait statues from the Athenian Agora excavations

Of the approximately 84 marble portrait heads found over the course of the Agora Excavations, about 22 (or 26%) represent female subjects. Seventeen of these are well enough preserved to assess their style of representation and to suggest their date of manufacture; I discuss a selection of these portraits here. Many of these heads, like much of the marble sculpture found in the excavations, come from contexts that are Byzantine and later in date, as huge quantities of broken-up marble objects were brought into the area to be used in the post-Antique period as building material.62 Portraits from such contexts cannot be said with certainty to have originally stood in the Agora. All of the portraits found in the excavations, however, likely come from the city’s urban core, which is itself a sufficient context for their inclusion in this study.

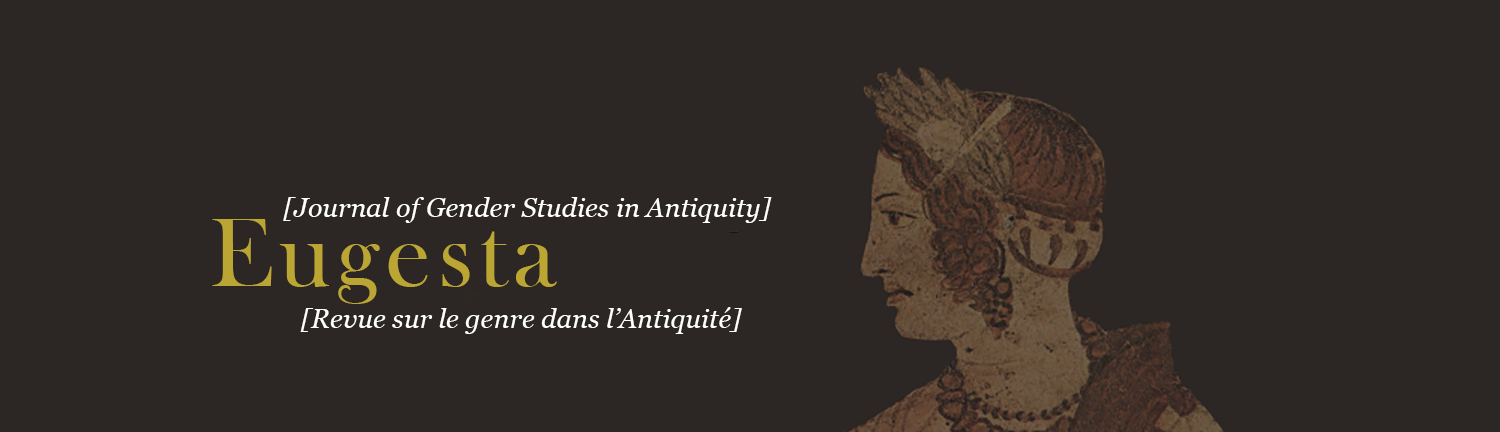

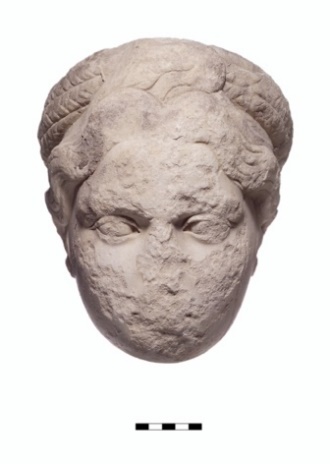

There are, however, a few female portraits that do come from authentically ancient contexts in the Agora; these examples provide additional information about the production and display of female portrait statues in Athens. The first is a very well-preserved head worked for insertion into a statue, found in a context dated to the second half of the third century A.D. (figs. 1-2). Two other fragments are associated with this head: a right forearm found nearby in Herulian destruction debris, and a right hand holding a phiale from a Byzantine context.63 The portrait represents a young woman, the head slightly turned to the proper right. The turn of the head, the large eyes, and the slightly parted lips give the subject an alert expressive attitude. The hair is parted at the center and the hair framing the face is arranged in a series of stacked, undulating waves. Behind the ears the hair is twisted into two rolled sections that are brought together at the nape in a ponytail. The face is a delicate oval shape, broad at the forehead tapering to the chin. The forehead is smooth and unmarked, with only the slightest break at the root of the nose. The eyes are large, and the pupils and irises are not engraved. The mouth is small and delicate, and there are few if any indications of age.

The style of the portrait—in particular its hairstyle—led Evelyn Harrison to date this head to the Julio-Claudian period and compare it to the portraits of Livia and Antonia Minor. While there are some vague similarities between these portraits, this simple hairstyle has a very long history at Athens. It is worn, for example, by many young women on Classical Attic tombstones,64 and it persists into the second century A.D. on a number of Attic grave monuments.65 The Agora head is also similar in its style and appearance to the head of the well-preserved statue of a Large Herculaneum Woman, which is dated to the Hadrianic period and comes from a cemetery in Athens.66 As Harrison herself noted, the hairstyle of the Agora portrait was less artificially styled than the comparative Roman examples and lacks the trendy forehead curls of Julio-Claudian females. In her description of the Agora portrait’s physiognomy, Harrison emphasized its strongly idealizing character and its classicizing elements: the smooth forehead, the thoroughly classicizing nose, with hardly a break in the profile, and the soft mouth with gently parted lips. Perhaps the portrait should be dated more broadly, with a terminus ante quem of the mid-second century A.D., when the eyes of most—although not all—Attic portraits begin to be engraved. The head and associated fragments were found very near the remains of an elaborate Roman-period Nymphaeum, which is dated to around the mid-second century A.D.67 This structure, semi-circular in plan, appears to have been decorated with statuary probably on two levels, much like the slightly later Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus and Regilla at Olympia. The fresh and unweathered surface of the Agora head suggests it stood in a protected display context, which the niches of the nymphaeum would certainly have offered. This statue, then, may have been part of the decoration of this elaborate fountain. Indeed, a female statue that held a phiale in the right hand was also part of the decoration of the Nymphaeum at Olympia, to which the Agora nymphaeum is strikingly similar architecturally.68

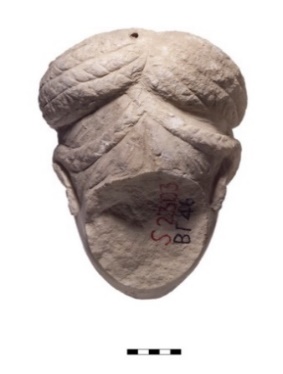

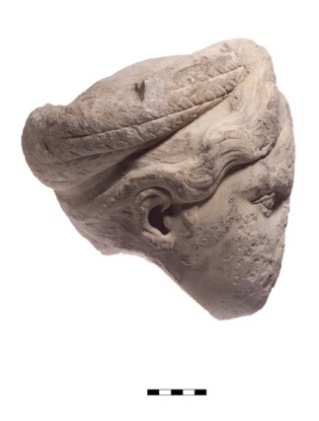

Two unfinished female portraits were found in contexts identified as sculptors’ workshops. Both portraits are dated to the second half of the second century based on their fashion hairstyles. The first69 (figs. 3-4) comes from post-Herulian clean-up debris in a well in a house on the west slope of the Areopagus, an area known for its workshops and industrial establishments.70 The portrait depicts a young woman wearing a Roman fashion hairstyle and a rolled diadem. The hair is parted at the center and arranged in a series of crimped waves framing the face. At the sides the hair covers most of the ears. The final design of the hair at the back, below the diadem, appears unresolved or at least not fully worked out. The hair above the diadem on the crown of the head is divided into four sections around the central part, in a modified version of the youthful “melon” hairstyle; the sections are then brought together in a large round bun. In its general outlines, the hairstyle is vaguely reminiscent of the first portrait type of Lucilla,71 and it also shares some details, such as the corkscrew neck curls, with portraits of Faustina Minor from Athens.72 The Agora portrait has a similar facial structure as these Attic portraits of the empress: the shape of the face, with the hair worn low on the forehead, the small mouth with full lips, the rounded chin.

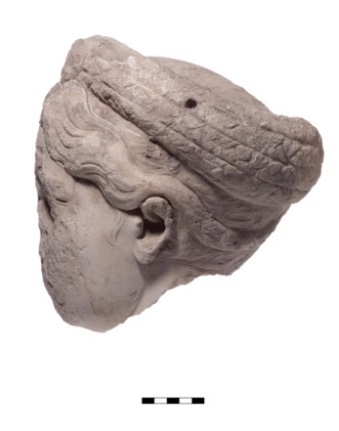

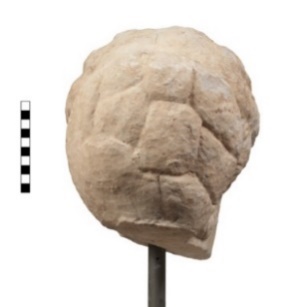

The second unfinished portrait73 (figs. 5-6) was found in Herulian destruction debris in a sculptor’s workshop located in a series of rooms on the southwest side of the Library of Pantainos.74 It depicts a more mature woman with her hair parted at the center, worn in finely crimped waves, and brought together in a braided bun at the nape. The simple hairstyle is reminiscent of, but not identical to, that worn by Faustina Minor.75 It is much closer in its details to a private portrait in the Capitoline Museum, which has also previously been identified as a portrait of Faustina Minor.76 Despite its semi-finished state, as Harrison noted, this is a strongly modeled portrait that imbues its subject with a forceful personality. Fully finished, this head would likely have been among the best of the Agora portraits.

The head was intended to be inserted into a draped statue, but for whatever reason the portrait was never brought to completion, as worked stopped just prior to the final stages of carving. Very little was left to be done. The hair appears to be nearly finished, except perhaps for the smoothing away of the two measuring points. The internal details of the ears have yet to be completed, after which the braces behind the ears protecting the delicate lobes would have been removed. The final smoothing of the flesh, and the removal of the chisel work on the face and neck has begun with the rasp work visible on the forehead. Fine work like the carving of the eyebrow hairs and the engraving of the pupil and iris in the very large eyes would probably have been some of the final details added to the face. Finally, the tenon would have been given its final shape during the process of fitting the head into the statue body. The tenon as preserved is much larger than one would expect or that one would require for fixing into a statue; the broad shape at the bottom was probably helpful for anchoring the head in place during the carving process.

The head of the younger woman shows a somewhat different sequence in the stages of working. Here the hair seems to be at a less advanced stage, with many of the internal details yet to be carved, while the face is more advanced, with a fine rasp finish that likely represents the surface before its final smoothing. It is interesting to note that the final smoothing of the flesh came after the carving of the eyebrows and the articulation of the eyes. The final shaping of the tenon would have come last, during the process of fitting the head into the statue body. Even in its semi-finished state, this portrait is impressive. As Harrison observed: “One has the impression that the lady represented, perhaps, an Athenian priestess, is well characterized and that the portrait, had it been completed, would have been a very good one.”77

The measuring points on both portraits clearly show the sculptors were working from set models, which suggests subjects of some importance. Klaus Fittschen has stated that non-imperial, “private” portraits with measuring points are typically of the highest quality.78 While neither subject can be identified, we do know that there were multiple portrait statues of the female members of Herodes Atticus’ family that stood in Athens. The subjects of these Agora portraits were likely members of a similarly elite, high-status family.

That women of such families were honored with portrait statues in the Agora is shown not only by the inscribed statue bases already discussed, but also by a fragmentary head found in 1933 in a Byzantine wall in the area of the Library of Pantainos (figs. 7-8). The head has been identified as a portrait of Athenais, one of the daughters of Herodes Atticus.79 This finely finished portrait, made of imported marble, depicts a young woman with large eyes, a full round face, and an elegant fashion hairstyle. The hair is worn in a series of crimped shallow waves on either side of the central parting, and spiral “kiss” curls in front of each ear. The lips are full and slightly parted. The eyes are rendered as if looking up and to the right; the larger area of unfinish in the hair on the right side of the head suggests it was turned in this direction.80 The way in which the head is cut and roughly finished on both sides and particularly on the back, as well as the dowel hole in the back upper surface, suggest the head may have originally been set into a veiled statue.

Harrison correctly recognized that the Agora head represented the same type as a portrait statue from the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus in Olympia. At the time, that is in 1953, the Olympia statue was identified as a portrait of Faustina Minor, as it had been found near an inscribed base naming the empress. Renate Bol’s later study of the Nymphaeum, published in 1984, argued that the Olympia statue was rather a portrait of Athenais, a daughter of Herodes Atticus.81 This identification is mostly widely accepted, and the type, known in three examples, has recently been published as such in Fittschen’s 2021 study of private portraits with replicas. Here he also suggests that all three portraits of Athenais may have been made in the same Attic workshop, the workshop that would also have made the better-known portraits of Herodes Atticus and Polydeukion.82

Like the portrait of Athenais, most of the female portraits found in the Agora excavations can be broadly dated to the second century A.D. based on their metropolitan fashion hairstyles. The quantity – and quality – of the portraits from this period is perhaps not surprising, as it is in the second century that the production of marble portrait sculpture came into its own throughout the Roman world.83 The wearing of hairstyles modeled after fashions originating in Rome is more commonly found in female portraits from Athens than it is in the contemporary male portraits from the city, which in their style of appearance appear to be more concerned with local ideas and interests. We see something similar at work in Roman-period Attic tombstones84 and in the portrait sculpture from Aphrodisias,85 where women were more likely than men to embrace Roman fashion hairstyles in their portrait statues.

Even when they do so, however, these female portraits tend to adopt the basic design or individual aspects of these fashion hairstyles, rather than follow them closely and with precision. For example, there is the fine portrait head of a young woman with an elaborate “turban” fashion hairstyle, found in 1970 in a Byzantine pithos in the northwest area of the excavation (figs. 9-12).86 The subject has a full round face, large almond-shaped eyes, and fleshy well-carved ears. The hair is parted at the center and frames the face in undulating waves. Above the central parting a series of upswept wavy locks of hair overlap the nest of braids. Worn behind the ears, the wave of hair framing the face is then braided and looped up and into the crown of braids at the back of the head. The coronet consists of four to five braids wrapped around the head in a turban-like arrangement that became particularly popular during the Hadrianic period.87 There are many variations on this basic hairstyle, principally in the arrangement of the hair over the forehead.88 There is, however, no exact parallel for the hairstyle worn by the Agora portrait; while certainly aware of recent fashion trends from the capital, the subject put her own spin on the style. As Bert Smith has argued, the adoption of contemporary fashion hairstyles in the portraits of women was “a means of showing participation in an Empire-wide culture of fashion and female elegance” rather than a statement of the subject’s political affinity to Rome.89

Another example of this local creativity in fashioning personal appearance is the beautifully preserved bust of the Hadrianic or early Antonine period of a young woman from a late Antique house on the slopes of the Areopagus (figs. 13-14).90 The portrait shows obvious Roman influences, but also a certain independence from central models as well as the hallmarks of local sculptural technique. The coiled bun placed high on the back of the head is reminiscent of the hairstyles of the empresses Sabina and Faustina Maior, but it is clearly not closely modeled on either. The hair framing the face, springing up over the forehead and combed back in long gently waving strands is an arrangement one rarely finds in female portraits in the West. Such a style does occur, however, in works from Athens and Greece, for example in a very high-quality fragmentary female portrait in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which reportedly comes from Athens and is dated to the late Antonine period.91 In addition, the careful carving with the chisel of the strands of hair framing the face in both portraits without any trace of the drill is characteristic of the finest Attic portraits of the Antonine period, at a time when most metropolitan Roman portraits deploy an ostentatious use of the drill.

Slightly later and a bit more in line with metropolitan fashions is the head of a woman found in 1992 in a Byzantine period context in the northwest sector of the excavation (figs. 15-18).92 The head, broken off at the neck, represents a young woman wearing a fashion hairstyle of the later second century. The hair is arranged in four crimped waves on either side of the central part, completely covering the ears at the sides, and then gathered into a very large bun that covers most of the back of the head. There are a series of wispy spiral curls on the sides of the neck behind the ears. The face is smooth and full, with a distinctly angular shape, unmarked by any signs of age. The eyes are very large, with heavy and sharply cut upper lids, set off from the lightly arched plastically rendered brows by a thin drill line. The irises are heart-shaped and hang just below the upper lids; the pupils are lightly incised. The mouth is small and turns up slightly at the corners. The full bowed lips are firmly closed. In profile the nose has a decided hook and the chin, although now chipped, was rounded. The hair framing the face follows the fashion set in the portraits of an Antonine princess, perhaps representing a sister of Lucius Verus,93 while the size and arrangement of the bun is similar to the portraits of Faustina Minor’s daughter-in-law Crispina.94

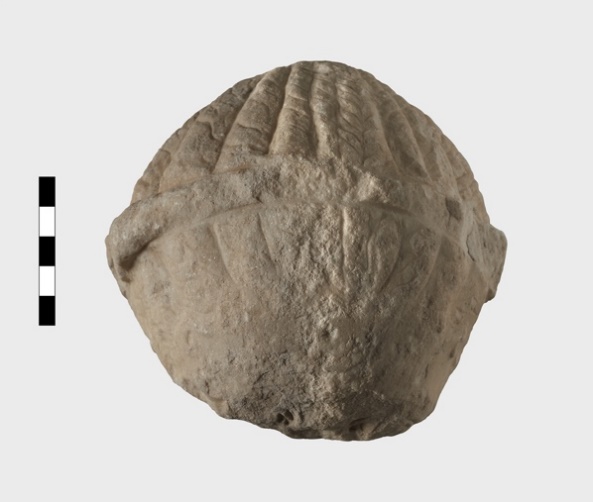

Finally, I include here a very fragmentary portrait of a young girl (figs. 19-20),95 given the prominence of statues of girls in the epigraphic evidence. The portrait sports the so-called melon hairstyle and wears a rolled diadem. The fragment was rescued from an Agora marble pile in 1977 and is currently unpublished. Unfortunately, only the top of the head is extant, although the inner corners of both eyes and the outer corner of the left eye are visible, and some sections of the forehead are preserved. The hair framing the face is divided into nine sections, with the central section forming a thin braid. There is a kiss curl at the right temple. The nine sections of hair above the rolled diadem appear to have been brought together at the crown of the head. While this is a much battered and small fragment, the few sections of flesh at the temples show the skin was once smoothly polished.

Is she perhaps a hearth-initiate? A much better-preserved head in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens provides a good example of what a portrait of a female hearth-initiate might have looked like,96 as does the beautiful portrait of a young girl in Pentelic marble said to be from Corinth in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.97 Both wear their hair in the melon style with the sections brought together in a high bun at the crown, and both wear rolled diadems. The head in the National Museum also sports what appears to be a myrtle wreath, an attribute that is worn by the portraits of young boys from both the Agora and Eleusis that have long been identified as hearth-initiates.98

Conclusions

While there are unfortunately no examples in which the epigraphic and sculptural evidence overlap, I would argue that considering both strands of evidence is crucial for understanding the female statue landscape in Roman Athens. For example, if one focuses only on the sculpture, we miss completely the important category of female hearth-initiate, whose statues are so prominent in the inscribed bases. It is also important to look across a range of contexts, as each appears to have its own chronological and honorific patterns. From the epigraphic evidence, it is clear that the Acropolis and City Eleusinion were important venues for female portrait statues beginning in the fourth century B.C., while at Eleusis honorific activity increases in the late Hellenistic period and in the Imperial period the sanctuary becomes an important venue for elite display. The Agora appears to remain throughout its long history a male-dominated space, as there does not appear to be any female statue monuments set up there until the second century A.D., and even then, their numbers are vanishingly small.

On the other hand, if we focus only on the statue bases, we are considering only one part of the monument and therefore miss taking into account the visual impact of the statues themselves. And the extant portrait sculpture tells us something important about local interests and concerns. For although it is assumed in much of the scholarship that Roman styles of portraiture were adopted in Attic portraiture already in the early Imperial period,99 the extant portrait sculpture suggests that Roman female fashion hairstyles only became common in the second century A.D., a pattern we also see in Attic tombstones.100 In addition, few of these female portraits embrace the so-called period face of Roman portraiture. Rather than individualizing physiognomic features and obvious indications of age, the portraits tend to favor the more classicizing facial features of ideal beauty.101 Finally, although it is customary in portrait studies to draw upon a wide range of evidence from a variety of cities – indeed, it is particularly hard to resist such a move when the evidence one has to deploy is either deficient or has significant gaps – I would argue that local concerns and ideas, local religious rituals, the local history of statue making, and the perceived importance of a particular display venue, which could change over time, profoundly shaped the practice and history of honoring women with portrait statues in Roman-period Athens.

Fig. 1

Female portrait head worked for insertion into a statue. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 1631. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 2

Female portrait head worked for insertion into a statue. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 1631. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 3

Unfinished female portrait head. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 1237. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 4

Unfinished female portrait head. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 1237. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 5

Unfinished female portrait head from the sculptor’s workshop in the Library of Pantainos. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 362. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 6

Unfinished female portrait head from the sculptor’s workshop in the Library of Pantainos. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 362. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 7

Portrait of Athenais, daughter of Herodes Atticus. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 336. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 8

Portrait of Athenais, daughter of Herodes Atticus. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 336. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 9

Portrait head of young woman with turban hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2303. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 10

Portrait head of young woman with turban hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2303. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 11

Portrait head of young woman with turban hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2303. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 12

Portrait head of young woman with turban hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2303. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 13-14

Portrait bust of young woman from late Antique house on the slopes of the Areopagus. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2437. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 14

Portrait bust of young woman from late Antique house on the slopes of the Areopagus. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2437. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Figs. 15

Portrait head of a woman with late second century hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 3423. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 16

Portrait head of a woman with late second century hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 3423. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 17

Portrait head of a woman with late second century hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 3423. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 18

Portrait head of a woman with late second century hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 3423. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 19

Fragmentary portrait head of young girl with diadem and melon hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2759. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).

Fig. 20

Fragmentary portrait head of young girl with diadem and melon hairstyle. Agora Excavations, inv.no. S 2759. Photo: Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (HOCRED).