Introduction

This article proposes a reflection on how new media art challenges the norms of exhibition lighting design. While new media art is a broad category with rather fluid boundaries, including various types of practices using electronic media technologies in an innovative way, such as Net art, interactive digital installations, computational art, robotics, this article focuses specifically on such work that is specifically made for presentation in a physical exhibition space, such as an interactive installation on show in a museum. Contrary to most other art exhibitions that call for a considerable amount of light, new media art exhibitions are often shown in darkness or subdued lighting.

In The Phenomenology of Perception, Maurice Merleau-Ponty states that perceiving things visually means perceiving light1; that seeing is seeing color and light. Light makes the visual qualities of objects – colors, surfaces and textures – sensible to the eye and is therefore a major factor in the aesthetic experience of any artwork. This is part of what Merleau-Ponty calls a “spatial configuration of perception”2, where different qualities are put into relation with one another and perceived simultaneously. In an exhibition, therefore, light is not to be treated as separate from other spatial characteristics since they form a single entity in the perception of the spectator. In addition to making visual qualities of objects appear, diverse light conditions allow us to see objects differently, light itself possessing distinctive qualities that are, in combination, inhabited by subjective meanings. Light not only creates the conditions for seeing and interpreting an object; it is itself subject to interpretation.

In an exhibition, light directs the viewer and directs their gaze3 and attention, it can valorize the exhibits or draw attention to some of them4, enhance the visitor’s visual comfort5, structure the exhibition space6, and help alleviate museum fatigue7. On the other hand, if its intensity is not correctly calibrated, it can irrevocably damage sensitive artworks8. Light can also guide the interpretation of an artwork9; for instance, by creating a specific atmosphere for an artwork to be seen in10. In the case of interactive digital installations light can also induce interaction or indicate a specific object to be used by the spectator. Designing a light environment requires both artistic and technical skill, an understanding of the physical properties of natural and artificial light and of its perceptual effects on the appearance of art and space.

While some of the abovementioned functions remain relevant in new media art exhibitions, others have changed or been entirely disposed of. By analyzing contemporary media art exhibitions in conjunction with how other artworks are shown, this article proposes envisaging darkness in the exhibition space as an aesthetic quality that can be worked with in order to create a specific context for the visualization of art. The first section of this article investigates two spatial settings for the visualization of contemporary art, the White Cube and the Black Box, together with their ideological and historical baggage. It argues that neither of these terms is fitting for the new spaces created by exhibition makers for new media art, and introduces a new term, the Dark Space, for discussion. The second part is more concerned with the aesthetic qualities of lighting in the Dark Space and argues that despite originating as a technical constraint for some artworks, it can also be an aesthetic choice. The last section is concerned with the introduction of light into the exhibition space in new media art exhibitions and elaborates on how exhibition makers break the postulate of darkness in new media art exhibitions.

Darkness in the exhibition space. The Black Box as a black White Cube?

New media art exhibitions are very often not held in a bright White Cube, the archetype for the modern exhibition space and the norm for the presentation of contemporary artworks in galleries, fairs, museums, festivals and alternative spaces alike11. They are shown in dim lighting. Such conditions of illumination can be viewed as relating directly to screening technologies. Video projectors, often used for these artworks, function better in darkened rooms, such as cinemas. Since video projectors use light in order to make images visible, any external source would disrupt rather than enhance the quality of the artwork. The paradigm is thus reversed: in order for the artwork to be visible in satisfactory conditions, instead of an appropriate amount of light, an appropriate amount of darkness is necessary. As Barbara Büscher points out, the darkness of these Black Boxes essentially provides the same neutrality as the whiteness of the White Cube: The black of the walls, ceilings, and floors, like the white of the White Cube, suggests neutrality, and ultimately the negation of concrete, physical space. Both place the spectator/viewer in a position of maximum concentration, of focussing their gaze, of blocking out the outside and focusing their attention.12

In the White Cube, all decorations are removed, creating an empty space with no obstructions or distractions. The White Cube further removes the artworks from any aesthetic or historical context, providing a supposedly neutral space for the perception of art. “The art is free, as the saying used to go, ‘to take on its own life.’13” Brian O’Doherty questions the neutrality of the White Cube. It would not be, as once presumed, a neutral space for the perception of art, but a highly ideological space. The aesthetic force of the white walls modifies the artworks and enters in direct competition with them. O’Doherty further argues:

The purpose of such a setting is not unlike the purpose of religious buildings – the artworks, like religious verities, are to appear “untouched by time and its vicissitudes.” The condition of appearing out of time, or beyond time, implies a claim that the work already belongs to posterity – that is, it is an assurance of good investment.14

Much like the White Cube, the Black Box is an undecorated space with little to disrupt the spectator’s direct contact with the work of art. As Büscher correctly points out, it focuses the spectator’s attention on the work. Does it, however, also freight the same ideological implications as the White Cube, or does it create a different semiotic setting for the appreciation of art? Is the Black Box, like the White Cube, recognized by the viewer as a space for the presentation of high art, inevitably turning every object within it into a desirable object of appreciation? Is the Black Box the same as the White Cube, but just in black?

Unlike the White Cube that avoids dramatic effects through even light distribution15, the Black Box, much like a theater space, throws them into relief. In his 2020 article “Interpreting Art with Light”, architect and light designer Thomas Schielke points out how the White Cube accentuates the minimalism of the exhibition design, whereas the Black Box deals in hyperreal, dynamic stagings. He goes on to attribute highly emotional, mildly mystical effects to the Black Box setting16. Dark exhibition spaces that can be called Black Boxes, however, are far from being one homogenous category of spatial settings. On the contrary, they can produce different aesthetic qualities, varying degrees of darkness, while subdued illumination can also result in different light temperatures and hues, ranging from cold, greenish tones to warm yellows, reds and oranges. Thus, the environment created by dark exhibition spaces may elicit very different emotional responses.

The term Black Box originated in the theater, where darkness forms the starting point of the artistic experience. Véronique Perruchon, researcher in theater studies at the University of Lille, points out the importance of darkness in the theater and to how it is manipulated as an aesthetic material:

In the last third of the twentieth century, black in theater is renewed and becomes a material with revealed aesthetic qualities. Black is not a simple background or an ornamental frame that accompanies a drama. It is a plastic reality, a component of scenic writing. Black is not neutral: it is sublimed by materials with reflective textures, or on the contrary worked in its opacity thanks to matte supports. It is made to exist as a setting, or as a partner. It is constitutive of the theater as a dramatic element of an aesthetic space. It is the reign of the ‘black box’.17

The darkness in the exhibition space can be manipulated in a similar way. Light qualities in combination with the material of the structures and surfaces can create a wide range of effects, from matt planes that absorb light and thus enhance the darkness, to surfaces that can be animated through reflection. As theater specialist Tina Bicât states, the role of lighting in theater is paramount; it “directs looks, attentions, and emotions.18” Just as on stage, in the museum context, whatever the type of space, light is not neutral, instead exerting a decisive influence on the perception of the exhibition space and of the artworks within it. What about the underlying ideological implications of the Black Box theater? Do they carry over into the Black Box exhibition space? Claire Bishop argues that the Black Box theater and the White Cube museum spaces are laden with different ideologies. She states that the White Cube, the “archetypal modern exhibition space,” “is a blend of neutrality, objectivity, timelessness, and sanctity: a paradoxical combination that makes claims to rationality and detachment while also conferring a quasi-mystical value and significance upon the work.19” Becoming popular in the 1960s in American universities, Black Box theater, was to jettison all artificial drapery and technology in order to facilitate the direct contact between the actors and the audience. It thus aimed to distinguish theater from television and cinema through immediacy, proximity, and communication20. Bishop continues to argue that the Black Box theater and the White Cube museum stem from different behavioral conventions21. While in Black Box theater the spectator is seated in front of the scene, the spectator in a museum is mobile. They can freely approach the works and decide on the duration of visualization, instead of having to sit through an entire performance22. Thus, while a stage performance lasts a fixed length, time in a museum is diffuse and depends on the appreciation of the viewer. In this regard, the Black Box museum space differs significantly from the Black Box theater. In the former, spectators can decide how long they watch a video or experience an interaction within an installation. The experience is thus fragmented. This fragmentation can be acknowledged and enhanced by artists, for example by making use of multi-screen installations where visitors not only choose the length of visualization, but also decides which the film clip they view. Though, the amount of time based media works in an exhibition can make it impossible to view the entirety of every video or experiment with every interactive installation in depth. That might cause frustration for viewers but is not necessarily seen as problematic by curators. Karen Archey, Curator of Contemporary Art for Time-Based Media at Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, states that it can be extremely liberating for spectators to get rid of the feeling that they have to see and understand everything within an exhibition for the experience to be worthwhile23. Because of these different spatial, temporal and behavioral conventions, the term Black Box cannot be translated one-to-one from theater to museum. It is questionable if the term Black Box is applicable to all museum spaces employing darkness or dim lighting. In art exhibitions, Black Boxes are frequently used in order to show video or film. The exhibition of film and video once was described by Raymond Bellour as a proliferation of Black Boxes in a White Cube24. Here the word Black Box refers to spaces that are relatively small and dark, having dark walls and showing a limited quantity of work. The spectator enters these spaces, generally through a light and sound trap that isolates the work from the rest of the exhibition.

The variety of spatial configurations can by no means be reduced to these two categories: the black and the white. While new media art can be found in such boxes or, less frequently, in the White Cube, exhibitions of these artworks can also employ spatial configurations that do not correspond to either of these types. Instead of consisting of a succession of small and confined spaces with only one or very few exhibits, they may take place in large halls allowing the artworks to enter into dialogue with one another. Though not invariably, these spaces may share characteristics with the White Cube, in that they can be open spaces with smooth, neat walls, flat wood or concrete flooring or carpet, possessing similar proportions, etc. For these large spaces the term Black Box does not seem to be appropriate. In the following, I will propose the term Dark Space in order to talk about this broad variety of spatial settings. In opposition to the Black Box, Dark Spaces may combine different degrees of darkness and present extremely diverse spatial characteristics. Abandoned warehouses, tunnels, bunkers, basements, etc. can be transformed into dark exhibition spaces with their own atmosphere, aesthetic qualities and emotional charge. These spaces are neither cubes nor boxes. While the White Cube displays distinct, clearly defined qualities, the Dark Space can combine various spatial qualities. The walls can be painted uniformly black, be built of raw concrete or of some other material, the ceilings may be high or low, they can have a wide range of proportions, etc. The smallest common denominator would seem to be the relative dimness of the space, the reduction of ambient lighting and light sources that are either directed onto the artworks or emitted directly by them.

Darkness as constraint and aesthetic choice

Even though darkness initially imposed itself as a technical constraint, it might also be the outcome of an aesthetic choice. It should be pointed out that technical developments have increased the power of video projectors and LED screens in terms of brightness and contrast, making them more suitable for used in ambient lighting. Nonetheless, some curators, artists, and exhibition makers embrace this darkness. This was the case for the installation of works by Marnix de Nijs, Cocky Eek and Carla Chan at the Conflux Festival at V2_Lab for Unstable Media, Rotterdam 202225. The exhibition program of this festival with the subject “exit human” focused on novel sensory experiences. At the V2_ the spectator entered the exhibition through a black curtain that functioned as a light trap, keeping all natural light out of the space. This in turn consisted of one room with a high ceiling, structured by two black columns. The walls were mostly covered with mat, black fabric which contributed to the darkened atmosphere by absorbing the light. Spotlights placed on the ceiling illuminated the work by Cocky Eek with blue and reddish light and the work by Marnix de Nijs with warm, white, yellowish light. The work by Chan used a video projection and thus itself functioned as a light source. Even though it remained relatively dark, different qualities of light were combined, creating a distinct atmosphere for the exhibition environment.

The information brochure of the exhibition reads as follows: “The overall exhibition stages a dark setting in which abstract and sensorial experiences are combined with concepts that arise when thinking of humans and their transformative relationship with technology, ecology, society and space.26” The exhibition makers thus highlighted darkness and its cognitive effects on the spectator. Two of the works directly benefited from this dimmer environment. Commissioned for the festival, Void by Cocky Eek (Figure 1 and 2) consisted of a large sphere made out of black cloth inflated from the inside. Visitors inserted their heads into the sphere through slits in its bottom quarter, their bodies remaining standing outside it. Inside, visitors were confronted with a complete darkness that first destabilized them and then revealed other sensorial experiences: a rotating speaker fixed in the upper part of the sphere within created an acoustic environment that circulated around one’s head. Whistling and hissing sounds could be heard, sometimes reminiscent of a steam train approaching and then moving away in a circular movement at a constant speed. The movement of air inside the sphere created by the machine continuously inflating the balloon was also perceptible. When other spectators moved the sphere by putting their head inside or pulling it out, the distortion of the fabric became tangible, creating a sense of presence even though it was impossible to see one another. After a while, some light coming through the slits became visible to the spectators. The outside of the sphere was made of dark but shiny cloth, reflecting the light of the projectors and increasing the presence of the sphere in the room. In that this immersive environment aims to exclude the vision in order to increase the spectator’s focus on the sonic experience, it clearly benefits directly from a dark environment.

While Void emphasized the darkness of the room, the video installation Drifting Towards the Unknown by Carla Chan (Figure 3) worked in contrast to it. Chan projected white light, evoking fluids in momentous or waves, on a rectangular screen. Smoke emitted from behind the screen plunged the exhibition into an unreal atmosphere. The smoke worked as an immaterial extension of the projection screen, slowly coming out of its surface and floating through the space while reflecting the bright, white light of the video. At the same time, the smoke blurred the projection, rendering it somewhat intangible. The brightness of the cold, white light created a strong black/white contrast in the darkness of the exhibition space. For the third work, AOR-200 Autonomous Oil Reserve, by Marnix de Nijs (Figure 4) there are no technical constraints for the exhibition in a dark space. However, the darkness of the room correlated well with the issues of surveillance and security raised by the work27.

Figure 1

Cocky Eek, Void, Immersive environment, 2022. Installation view, Conflux Festival, June 2022.

Photograph by the author

Figure 2

Cocky Eek, Void, Immersive environment, 2022. Installation view, Conflux Festival, June 2022.

Photograph by the author

Figure 3

Carla Chan, Drifting Towards the Unknown, AV Installation, 2022. Installation view, Conflux Festival, June 2022.

Photograph by the author

Figure 4

Marnix de Nijs, AOR-200 Autonomous Oil Reserve, 2018. Installation view, Conflux Festival, June 2022.

Photograph by the author

V2_’s exhibition space, which is actually also the institution’s production space and used for artistic experimentation, is very flexible and can, on occasion, be transformed into a more conventional White Cube space. For lighting, the V2_ uses a custom-made theater grid. A lighting grid is a system of perpendicular crosshatches of pipe fixed under the ceiling above a stage or scenery. It allows the spotlights to be fixed at different angles. In comparison to conventional museum track lighting, the cross connections of grids provide for greater flexibility. According to Michel van Dartel, director of V2_, this allows the space to create different lighting environments more readily, especially for objects placed within the space and not along the wall. V2_ also uses the grid to fix projection material at uncommon angles or tracking devices for interactive works28.

In the theater today lighting poles are used mainly to support or load scenic elements and spotlights. Fixed under the ceiling parallel to the stage, these mobile poles can be raised and lowered independently (without the constraint of a perpendicular tube holding them together) and thus facilitate lighting not only at different angles, but also at different heights. In addition, theater spaces also have at their disposal a wide distribution of electrical circuits, making it possible to multiply the locations of each spotlight. Some institutions, like the Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains – make great efforts to achieve a flexibility similar to a theater stage, but with different technical means. Others, like the ZKM, successfully accommodate more traditional museum track lighting.

Up to a point, the exhibition at V2_ exemplifies how curators and light designers are able to deploy various kinds of lighting dark environments. The darkness is not only a constraint; it can be worked with in its materiality and quality in order to create very different atmospheres for the display of the works. It enables the creation of highly specific aesthetic environments that allow the spectator to focus totally on the works and heighten their emotional response. This type of spatial set up, with few structural elements and no or very little ambient lighting is also used at different venues exhibiting digital or new media art like the Fresnoy or the Ars Electronica Center. In comparison to the use of Black Boxes, these spaces enable spectators to see several artworks at once, sometimes even every one in the exhibition, allowing for easier circulation and for the works to be confronted with one another. At the V2_ exhibition, the dark cloth hung from the walls absorbed the light and further obscured the space. In such Dark Spaces, the spatial impression of the gallery is created more by the artworks than by the constructive parts of the space, like walls, floor, ceiling, etc., that disappear into the darkness. The relation between artworks and exhibition space is thus minimized. If the viewer’s gaze is directed by a strong light-dark contrast, what should not be visible, such as cables or technical devices, can be made invisible. As in the White Cube, artworks may appear out of space and out of time, but since the ideological implications are different, the impression of being confronted with precious works of timeless art, as it has often been stated for the White Cube, is not necessarily conveyed. These Dark Spaces can vehicle a strong vibe of experimentation and foster direct contact with the works. Such exhibition spaces can elicit a wide variety of emotional responses among visitors to the same exhibition, ranging from a calming, relaxing effect, to excitement or even anxiety. The fact of being somewhat isolated from the space by the darkness increases the visitor’s focus on the artworks. This does not, however, make the perception of the artworks autonomous from the space. It cannot be considered as neutral. On the contrary, the contrast between light and darkness imparts dramatic effects to the exhibition, whose overall atmosphere influences the perception and interpretation of the works within it.

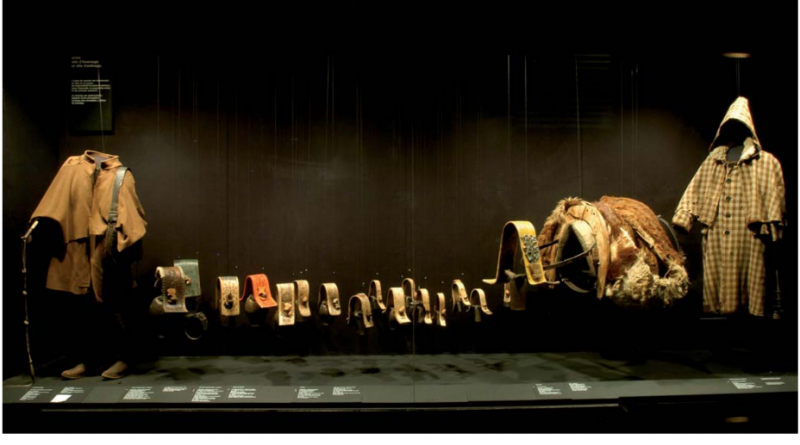

Subdued lighting is not entirely new to museums. It is already known from the exhibition of fragile materials, like prints, drawings or textiles. There exist though exhibitions whose space also shows some of the above mentioned characteristics, namely dark walls, lighting directed directly onto the exhibits, little or no ambient lighting, but without such technical constraints. Light designer and author Jean-Jacques Ezrati mentions La galerie culturelle (Cultural Gallery) of the Paris Musée national des arts et traditions populaires (MNATP, National Museum for Traditional and Popular Arts, Figure 5) as one historical example. Here the space of the exhibition was dark, lit only by the spots placed in the showcases directed towards the objects. Like in the performing arts, where the light tells the spectator where to look at by creating visual hierarchies on the stage, the spots direct the spectator’s eye towards the exhibits and, at the same time, showcases them. The architectural elements painted in black fade into darkness and allow the spectator to concentrate on the exhibition objects. On the other hand, such dark spaces may diminish visitors’ visual comfort by impairing color rendering and making the reading of wall texts and labels more difficult, especially for older visitors.

A contemporary example of such an exhibition space is to be found at the Rijksmuseum (Figure 6), where part of the ground floor uses a similar museography for the exhibition of keys, delftware, music instruments, jewelry, Dutch porcelain, relics, weapons and ship models. Here again, the exhibits, especially the white delftware and porcelain, stand out against the black background so the spectators’ attention is center wholly on the exhibits. These examples show that in addition to being necessary for certain technologies or materials, dark exhibition spaces can also be an aesthetic choice, chosen for the specific visual effects they create.

Figure 5

La Galerie culturelle du MNATP: Section «Élevage», vitrine : «Ordre de marche d’un grand groupe de transhumants vers 1960», 1975

© MuCEM (Danièle Adam)

Figure 6

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, ground floor. Installation view, June 2022.

Photograph by the author

Brining Light to new media art exhibitions

Even though dim lighting seems to be a norm in new media art exhibitions, this does not prevent exhibition makers seeking to introduce light into exhibitions and media artists wanting to show their works in a substantial amount of light. The subject of lighting came up quite naturally in some of the interviews I conducted with museum officials. Karen Archey for example stated that they were trying to find a balance between darker and brighter spaces in the exhibition of Hito Steyrl’s works (“Hito Steyerl: I will survive”, January 29 – June 12 2022). The wish to alternate between spaces with different degrees of darkness and lighting directly informed the succession of the different works in the exhibition29. Arranged sequentially, the exhibition followed a fixed route on the ground floor, generally showing one work per room. Numerous video works, mostly on TV screens, were shown in a large space on the first floor. After an initial installation in the foyer in daylight, a succession of rather dark rooms dominated by red or blue lighting followed. Around the middle of the exhibition path on the ground floor there was again a room with some daylight. Here the work Mission Accomplished: BELANCIEGE (2019) was exhibited. The windows were sealed off with blue foil with BELANCIEGE written on it. Even though this space was not very bright as such, it allowed visitors to feel a significant change in atmosphere in contrast to the darker space they had been in before. Here spectators could sit and watch one of the smaller, calmer and less immersive works in the show presented frontally on three TV screens. Then again followed a succession of darker, more immersive spaces. The course of the exhibition ended with a brighter space on the first floor. The amount of lighting in the room can be related to the screening technology employed: the spaces with a larger amount of light in the exhibition showed mainly works on screens, whereas the darker spaces contained video projectors. As itinerant exhibition, the show has already been held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (19 May – 5 July 2021). Here the works were shown in a different order, but the show also included several spaces with daylight and alternated darker and brighter spaces.

Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman use the term hyperaesthesia for situations in which senses are stimulated to a point that they short-circuit our capacity to reason and make sense. Hyperaesthesia results from “the projection of informational overload [that] force a sense as much as to render it insensible30.” Deploying a variety of moving images, sounds and interactive propositions, media art exhibitions can be highly stimulating, even over-stimulating and thus tiresome for the spectator. This may cause visitors to lose interest and the ability to focus on the artworks. Integrating brighter, calmer spaces may break visitor immersion, allowing them to refresh and refocus their attention. They allow the spectator to rest and to recharge before being re-immersed in a dark space. The alternation of brighter spaces therefore might remediate problems commonly associated with dark spaces, such as increased tiredness or anxiety.

Other new media art exhibitions integrate daylight in areas specifically created for resting (Figure 7 and 8). Morgane Stricot, conservator and Head of Digital Conservation at ZKM, stated in an interview that the ZKM has introduced rest areas into their exhibition. These areas combine daylight, reduced noise and comfortable seating possibilities for the spectator to relax. She states:

[In the exhibition] we try to combine quiet spaces with light. We put catalogs, books about the artists, brochures and plans of the exhibition on the disposal of the spectator in these areas. (…) In “Art in Motion. 100 Masterpieces with and through Media” (July 14, 2018 – January 20, 2019) there was a kind of library with books about the artists and the artworks. That worked very well. The visitors took a lot of time and read about a particular artist. This material allowed them to learn more about the artist and the context in which the work was made. It also helps to show how the work has been exhibited before or in other contexts. For “Writing the History of the Future” we will also set up QR codes making explanations available on smartphones.31

Here, the use of daylight differs from that in the Stedelijk. In one case brighter spaces are integrated into the exhibition at specific moments, when the artwork on display allows for increased illumination. Thus, spectators can benefit from the positive effects of daylight, but without interrupting the course of their visit. In the other case a space specifically dedicated to rest is created with an atmosphere that encourages relaxation and study, allowing the spectator to pause and reboot during the exhibition, all the while taking time to inform themselves more deeply about the artworks on display.

Figure 7

Two Rest areas with daylight at the exhibition “Writing the History of the Future”, July 14, 2018 – January 20, 2019, ZKM, Karlsruhe.

Photograph by the authors, artworks visible in the pictures have been made unrecognizable at the request of the museum.

Figure 8

Two Rest areas with daylight at the exhibition “Writing the History of the Future”, July 14, 2018 – January 20, 2019, ZKM, Karlsruhe.

Photograph by the authors, artworks visible in the pictures have been made unrecognizable at the request of the museum.

When I interviewed Michel van Dartel in 2022, V2_ was in negotiation with their landlord because they wanted create a larger window area on the ground floor. In the domain V2_ is active in – the crossover between art, technology and science – there is an immediate temptation to create dark spaces for exhibitions, especially for screen-based art. The resulting display areas often feel closed off from the surrounding environment. Without entering it is hard to get an idea of what is going on inside. This in turn influences the types of artworks produced for these spaces. Van Dartel thinks that the domain somewhat should mature from this reflex, from darkness as a new spatial norm32. Not only is it technically possible today to project under very different ambient conditions and on very different surfaces, including glass, cloth or surfaces that are not flat, but art productions in new media are much more pluriform and concern a variety of supports that are not screen based. Opening up the space not only allows more light to enter; it also ensures a direct connection with the surrounding area on street level. Passersby can then look inside and inform an open dialogue with the artists and the artworks. This opens up the possibility of imagining a new type of space, one that would move beyond the conventional dichotomy of White Cube and Black Box, a space that would not only influence how artworks are seen within it, but also change what type of artwork is produced for it.

Conclusion

Darkness has become a new norm for the exhibition of new media art. Even though it started out as a constraint, it can now also be implemented as an aesthetic choice. As in the theater, darkness can be used as a material to work with. Different hues and temperatures of light can be deployed to create a variety of atmospheres; likewise with the material covering the surfaces of the exhibition space. The exhibition area borrows effects known from the theater in terms of how it directs the spectators’ gaze and focuses their attention. Some artists choose to show their work in very dark spaces, even though there are no apparent technical constraints, because darkness creates a type of intimate environment that heightens emotional response. Artists and curators are now working to go beyond this tenet of darkness by introducing light into the exhibition space or even by opening up the space entirely. Darkness in the exhibition space for new media art exhibitions is in turn being challenged by these developments.

Much investigation into this subject remains to be done. The scope of this article did not allow us to analyze in depth how these norms and conventions developed historically, how one artwork is perceived differently under diverse lighting conditions, or how spectators react to particular light environments. The subject also leaves room for collaboration among academic disciplines, allowing us to reflect on the crossover of states of museum lighting with those of the stage on a theoretical level. This permeability already exists among professionals, since lighting designers work for both the theater and museums, while people trained in the performing arts are also active in museum lighting design. As the boundaries of exhibition lighting continue to shift and expand, the exploration of these topics promises to yield valuable insights into the evolving world of new media art.