Introduction

Several years ago, the use of new media technologies was almost exclusive to pioneer artists, their exhibition limited to some institutions and festivals, often specialized and founded especially to this end. The artistic use of digital technologies took place mainly outside of established museum institutions and was ignored by the general public. Today the situation has very much changed. Digital technologies are everywhere, including in the Arts. New media is no longer reduced to a small group of people but more and more artists engage with it sporadically or on a regular basis. Artists are not bound to one means of expression but may shift between different media, searching for a way to express their artistic intent. To an increasing degree, artistic production is entangled with digital media. Sometimes this can be invisible in the final artwork, but artists also make use of the intrinsic qualities of new media technologies in a way that may challenge the institutions responsible for the collection and exhibition of art.

Many institutions of varying sizes and vocations have been exhibiting new media art1. However, there still are many for which the exhibition, collection and preservation of this kind of work represent a challenge. It seems like the digital divide has shifted from the level of the individual artist to that of those institutions, which are traditionally charged with the collection, exhibition and preservation of art. There is a huge gap between art institutions that have been gaining experience for years in the exhibition of new media art, whose officials have sometimes been active in the discussion of related issues, and those who have not.

This gap is also visible in the North of France, a region with a high density and variety of museums and art institutions. There are many types and intensities of engagement with new media art, from the creation of specific institutions, such as Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains, but also frequent or occasional exhibitions, or even little engagement with new media technologies. Based on a keen observation of Hauts‑de‑France art institutions, research conducted in this field, interviews with artists, conversations with conservators and museum officials, this article investigates the gap between our art institutions. It examines the spatial, administrative, and technological conditions for the exhibition of new media art. What are the curatorial strategies in specialized institutions like the Fresnoy, how are they organized, and what can other institutions learn? What are the reasons for this persisting division at a time when digital technologies are omnipresent and ubiquitous?

This article proposes two lines of reflection that can help explain why some venues engage more easily with art using new media technologies than others. Using the Fresnoy as an example, the first approach examines the curatorial practices of the venues. Several links are established between the spatial modeling, the administration, and the technological equipment of the Fresnoy and venues for the performing arts like theaters and opera houses. The second approach deals with the collection or the lack of activity in this field. Indeed, the venues that have pioneered in the exhibition of new media art often do not have collections, the zkm in Karlsruhe, Germany, being a major exemption. The last chapter of this article investigates the idea that it can be easier for institutions without collections to engage with new media art than for museums with collections.

Before looking on how specific institutions engage with new media art, I would like to take Claire Bishop’s famous 2012 Artforum article on the digital divide as starting point to retrace the debate about the marginalization of new media art and draw a nuanced picture of the situation between the 2000s and today.

Some observations on the digital divide in art institutions

Several years have passed since Claire Bishop wrote her famous essay “Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media” for Artforum. In this article, she argued that there were very few artists who critically questioned new media technologies through their artistic practice outside of a sphere of media artists. There was little overlap between these media artists and what Bishop called the mainstream art world2. She saw a gap between digital technologies and their use in art production. While “most art today deploys new technology at one if not most stages of its production, dissemination, and consumption”, she stated that “digital media have failed to infiltrate contemporary art3”. Her article provoked a strong reaction in the media art community, which had been questioning and critically analysing the technologies that Bishop addresses in her article for years, if not decades. Although she recognized that “there is, of course, an entire sphere of ‘new media’ art”, she insisted that this comprised “a specialized field of its own4”, one which Bishop decided not to consider in her article in order to focus on what she called the “mainstream” art world.

Indeed, the history of new media art has mainly taken place outside of established institutions5. Media artists and curators have created their own venues dedicated to exhibiting their art. Since the end of the 70s, media art festivals have been established all over Europe, beginning with the Ars Electronica in 1979 in Linz. This annual festival deliberately mixes innovative media art with recent advances in science and digital technology. Others followed, such as the Transmediale in Berlin (founded in 1988) and the Dutch Electronic Arts Festival (deaf, 1994‑2014). Besides festivals, specialized institutions were established dedicated to new media art, such the v2_Institute for the Unstable Media founded in 1981 in Rotterdam, the Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (zkm) founded in 1989 by media artist Peter Weibel in Karlsruhe and the Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains, founded almost 10 years after the zkm by Alain Fleischer. All of these venues participate in distribution and help promote awareness of new media among the general public. In the early 2000s, large established institutions began to show greater interest in developments in new media art and started collecting or exhibiting new media artworks. Among them, Tate was one of the first to initiate a net art programme, collecting 14 pieces between 2000 and 2011. The Guggenheim followed Tate in the exhibition of new media art, buying net.fleg by Mark Napier in 2002. Mainly in American institutions, major exhibitions of new media art also began to take place, such as 01010101 in 2001 at the sfmoma, Bitstreams in 2001 at the Whitney Museum of American Art and Seeing Double in 2004 at the Guggenheim6.

Nonetheless, when Bishop wrote her article in 2012, most new media art that reflected critically on digital technologies was still being realized at the margins of the art world while receiving very little visibility. This issue has been addressed and discussed by new media artists, curators and theorists such as the academic and curator Christiane Paul. In her 2008 article “Challenges for a Ubiquitous Museum: From the White Cube to the Black Box and Beyond”, Paul describes the position of new media art as that of a “ghetto”. Paul uses this term to qualify the separation of new media art from “more traditional” art practices and the uneasy relationship between art institutions and digital art forms7. Paul argues that one of the main means of relieving new media from its marginalized position would be to broaden its audience. The typical audience of new media art events such as festivals are generally “knowledgeable about the field and not especially diverse”. In contrast, a typical museum audience is generally composed of people who are not necessarily familiar with digital technologies, who might need assistance navigating and interacting with media artworks or who might even have a “‘natural’ aversion to computers and technology and refuse to look at anything presented by means of them8”. Paul suggests that, at the time of her writing, new media art was marginalized by museum institutions, which largely either ignored new media artworks or placed them in special lounges or cabinets, thus separating them from the history of art represented in the museums’ galleries9. However, it also seems that, around 2010, the marginal status of new media art was beginning to change. In 2010, Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook, both researchers at the University of Sunderland (uk) and independent curators at the time, published a series of interviews for the 10‑year anniversary of Curatorial Resources for Upstart Media Bliss (crumb), a research group and professional network for academics, artists, curators and all those working with new media art. As part of the introduction to this book, Cook and Graham asked nine new media curators “how the practice of [curating] new media art [had] changed in the past ten years10”. One recurring response was the observation that new media had become ubiquitous in art practice. For instance, Magdalena Sawon and Tamas Banovich (then owners of the Postmasters Gallery, ny) stated that “new media art entered the mainstream of visual culture over the last decade, [and] curatorial practice in the field has naturally shifted towards the center from a niche, separate territory11”. Barbara London, founder of the video art collection at the moma, answered that “artists [today] work with the latest technologies as readily as they sip water. Their tools are affordable and in the economic downturn collectivities are active again12”. Meanwhile, Rudolf Friedling noted that “new media art is now an established practice with a wave of recent art and media historical publications that needs to come to terms with the fact that the tools of new media are in everybody’s hands13”.

In early 2010, however, the acceptance of new media art in the art world was not as widespread as these citations might suggest. Statements indicating that new media practices had not yet arrived at the centre of the art world can just as easily be found. Annet Dekker, for example, a new media art curator based in the Netherlands, described new media art as mainly taking place outside of established art institutions in a statement on the crumb network mailing list:

Although curating digital artworks in physical spaces and online exhibitions is becoming more widespread, such exhibitions are mostly taking place outside of the world of traditional art. Currently a new generation of curators is organizing exhibitions in old warehouses, family homes, small side-street galleries, or online. They use existing curatorial formats for these presentations, adapting them if necessary, or even creating new ones14.

Thus, it can be said that by the early 2010s, new media art had taken a step out of the “ghetto” and into the art world, but it had not yet reached the centre. The demarginalization of new media art was and continues to be an ongoing process. However, the status of new media art had changed significantly by this time, as it was increasingly gaining attention from establishments such as art institutions and journals, as the very publication of Bishop’s article in the mainstream art journal Artforum attests to. In the present day, digital technologies are no longer just an alternative to conventional art practices, but to an increasing degree are the foundation of all art production15.

Today, small and large institutions regularly include media artists in their temporary exhibitions, and many new media exhibitions take place in recognized mainstream art institutions, such as 123 Data at the Fondation edf and Robots at the Grand Palais, to mention only two rather recent examples which took place in Paris. It has also become easier for artists to gain access to specialized knowledge through avenues such as residency programmes in research labs (including Arts at cern, La Diagonale at the Paris‑Saclay University and the airlab at the University of Lille, among others). “New media is out of the ghetto”, as media artists Christa Sommerer declared during a panel discussion Digital presentation strategies and collections which was part of the 2018 Ars Electronica conference programme. At the same event, she also stated that the preservation of new media art would henceforth no longer be a problem, arguing that institutions such as the zkm would soon be well equipped to preserve and exhibit art with strong technological components and be able help other institutions which did not have the same practical knowledge.

Indeed, many difficulties that were encountered in exhibitions of new media art in the 2000s and that have been discussed by curators and researchers such as Christiane Paul, Jon Ippolito, Steve Dietz, Sarah Graham and Beryl Cook seem today to have been overcome or at least significantly reduced. However, even though the “revolutionary phase of the information age is over and its newness is gone16”, I would argue that there is still a considerable difference between those institutions like the zkm which have decades of experience with new media art and those for which it is still uncharted territory.

So, how is the situation like in the Hauts‑de‑France? In 2020 a consortium of researches directed by Réjane Sourisseau, Victoire Dubruel, and Antoine Carton and financed among other by the region Hauts‑de‑France and the Direction régionale des arts contemporains (drac)17 published a report on the state of contemporary art in the region18. This research project aimed to better understand the socio‑economic situation of actors in the Visual Arts, including as well as individual artists as a variety of organizations producing or exhibiting art, etc. A first objective was to inventory actors in the sector of fine arts and to map their geographic distribution. That revealed difficult because of the lack of a common definition or generally accepted criteria of what can be counted, understood as an artistic institution. Then the research project studied the economic situation and relations among these actors in order to better understand the state of the ecosystem of fine arts, its functioning and development potentials.

- The methods of enquiry were as well quantitative and qualitative. They included for example informations from l’insee (National Institute for statistics and economic study). Two questionnaires one for artists and one for institutions were distributed online, 480 artists and 109 institutions replied. The qualitative methods included individual interviews and online research. The report pointed out a large diversity in the contexts and locations for the exhibition of contemporary art. It underlined the importance of associations and benevolent activities in this region. Even though it has a number of public institutions, like three museums dedicated to the Art of the 20th and 21st century, two Fonds régional d'art contemporain (frac, regional fond for contemporary art, public collections of contemporary art), four art centres, Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains, which I will talk about in length later on, four art schools and around thirty municipal‑schools, the fine arts sector is, according to the authors, marked by the activities of individual and collective associations. The report pointed out a large diversity of actors in this sector, often combing several functions: production and exhibition of art works, mediation, education, artists support, etc. Geographically, there is a concentration in the metropolitan area of its capital, Lille. The report also points out that there is a lack of circulation between the north and the south of the region as well as between its urban poles and rural zones.

- In multiple choice questions artists were asked to select up to two media they work the most frequently with. Traditional media, painting (33,3%), sculpture (24,2%), drawing (19%) and photography (18,3%) arrived at the top of this classification. Digital art, with 5,4%, 10th position, is situated in the middle of the rather exhaustive list of 23 media19. Digital art however is an umbrella term with an uncertain and fluid definition. The authors did not specify what actually falls under their definition of digital art, thus there is a uncertainty of which art practices actually fall under these 5,4%. Digital video or digital photography, which are sometimes counted among digital art would here rather be in the categories photography (18,3%) or video art (6,9%), digital installations however can be as well installations (15,8%) or digital art. Web design and video game design also are independent categories with respectively 5,00% and 0,00%.

I wanted to know how art, in the sense of Christiane Paul, using digital technologies not as a tool, but as a medium is represented in art institutions, exhibitions and collections, especially in the Hauts‑de‑France museums. The questionnaire for the institutions sent to me by the researchers shows that institutions were also asked with which media they worked with most frequently. However, there is no indication to how regional art institutions answered this question in the report. Some venues show new media art in the metropolitan area of Lille, but also in the rest of the region Hauts‑de‑France. Besides, Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains, an art school specialized on new, digital image technologies, there are several other venues showing new media art in the metropolitan area of Lille. L’Espace Croisé, an art centre in Roubaix, frequently shows digital art, among which works from former students from the Fresnoy. La Gare Saint‑Sauveur, a rehabilitated train station used regularly for art exhibitions and popular festivities, shows this kind of art. The University residency programme airlab allows artists to be hosted for three months in a scientific lab of a university partner in order to produce a work of art. The resulting works, that often can be qualified as digital art or new media, are also exhibited, generally in an exhibition spaces belonging to the university. The art space run by the city, L’Espace Le Carré, frequently showing video and installation art, exhibited a work using an augmented reality application once in 201920. The festival Safra’numériques for new media art in Amiens has programmed its 5th edition in 2021. In Jeaumont, a city of around 10 000 inhabitants there is La Gare Numérique, a cultural centre dedicated to digital technologies with a Fablab, exhibitions, concerts, workshops initiating children to technology and artist residences. Finally, a master programme called Scènes et images numériques combines visual arts and digital creation at the Université Polytechnique des Hauts‑de‑France at Valenciennes21.

Most interestingly, the venues most frequently engaging with new media art do not have collections. In an e‑mail enquiry I contacted three Art centres, the two fracs of the region and twenty nine museums having contemporary art in their collection listed by the Rapport des arts plastiques en Hauts‑de‑France in the attempt to find out whether these art institutions do exhibit or collect new media art. The received responses seem to suggest that there is indeed a bigger diversity in the media exhibited than in the media collected. While many of the responding institutions exhibit video, most of them do not exhibit new media art or not very frequently22. Some of them occasionally exhibit new media art or have future projects including this kind of art. The Musée du Touquet Paris‑Plage exhibited a work using augmented reality in a monographic exhibition on the graphity artist Speedy Graphito. The Musée départemental Matisse at Le Cateau‑Cambrésis had an exhibition in 2019/2020 La créativité demande du courage showing works from pupils in art schools in the region including several works with augmented reality or virtual reality. Les Musées de Soissons (l'Arsenal, musée d'art contemporain; le musée d'art et d'histoire Saint‑Léger) are planning an exhibition on digital art curated by Clément Thibault in autumn 2021. However, this enquiry seems to indicate that new media art is most frequently exhibited in art venues not having a collection and new media art is actually very little represented in collections. This research indicates that the digital divide has shifted. There is a bigger diversity in the media exhibited by art institutions than in the media collected. The following section will take Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains as an example in order to take a closer look on how an exhibition of new media art can be curated. The final section then will investigate the collection of new media art.

A theatre for the exhibition of art: Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains

History and mission statement

Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains is an art school containing a cinema and exhibition venue that opened in 1997 at the proposal of Dominique Bozo, head of fine arts at the French Ministry of Culture, and Alain Fleischer, film director, artist and eventual director of the Fresnoy, a position he holds to this day. It was established with the aim of creating a place in France for the production and diffusion of artistic practices using audiovisual and digital technologies. It was to be a space for practices combining artistic experimentation and innovation with the newest technological advances, a “high tech Villa Medici, an electronic Bauhaus, an ircam23 of visual arts24”. At first, the artistic productions of the Fresnoy were primarily focused on film and video, but they would later also include digital installations and environments.

The institution is housed in the former building of a popular leisure complex that operated between 1905 and 1984 and included a cinema with 1,000 seats, and a hall that could be transformed into a riding ring or hall for dancing, roller-skating, games and boxing tournaments welcoming up to 6,000 visitors. The building was remodelled in the middle of the 90s by Swiss‑French architect Bernard Tschumi. Since the available budget did not allow for a total reconstruction, the former leisure complex was included within a new construction with a total size of around 11,000 square metres25. Tschumi added a new front building, which today houses the entrance, ticket office and book shop, as well as some of the administrative offices and rooms used by the art school. In addition, he created a new roof which covers both the old and new sections of the building. Inside, the part of the complex accessible to the public consists of a succession of two halls, the Petite nef and the Grande nef, which are used as exhibition spaces, and two cinemas with 206 and 96 seats, respectively. The facilities of the art school also include a film set, a fab lab, a photo lab, laboratories for research and post-production and office spaces.

Financed by the French Ministry of Culture, the Region Hauts‑de‑France and the city of Tourcoing, the school offers a two‑year postgraduate programme for French and international artists, some of whom are generally recent graduates of master’s programmes, while others are more - or less - established artists joining the school with a clear project in mind. Each year, 24 students under the age of 35 hailing from all over the world are admitted to the programme. While benefiting from the school’s facilities, the students receive an €8,500 annual stipend for the production of an artwork. Furthermore, the Fresnoy offers access to a network of university science laboratories and private companies in the region that may contribute to the artistic production. Indeed, many works are produced in collaboration with researchers or specialists working in or outside of academia. The Fresnoy thus produces 50 works a year, 48 of them by the students and two by visiting professors who work with the students throughout the production process until the works are exhibited. Students generally produce a film in their first year and a digital installation in their second. The visiting professors have around twice the production budget of the students. As producer, the Fresnoy keeps these works in storage for two years, or sometimes longer, before releasing them to the artists. This might help to understand why some institutions do not engage with this kind of art or exhibit it only sporadically. The institution also owns the exhibition rights and rights for the reproduction of images of the works.

Spatial conditions

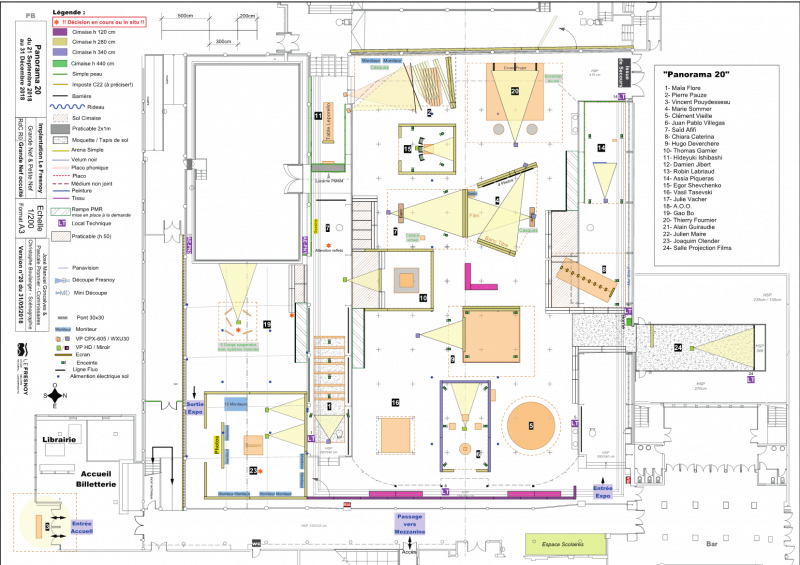

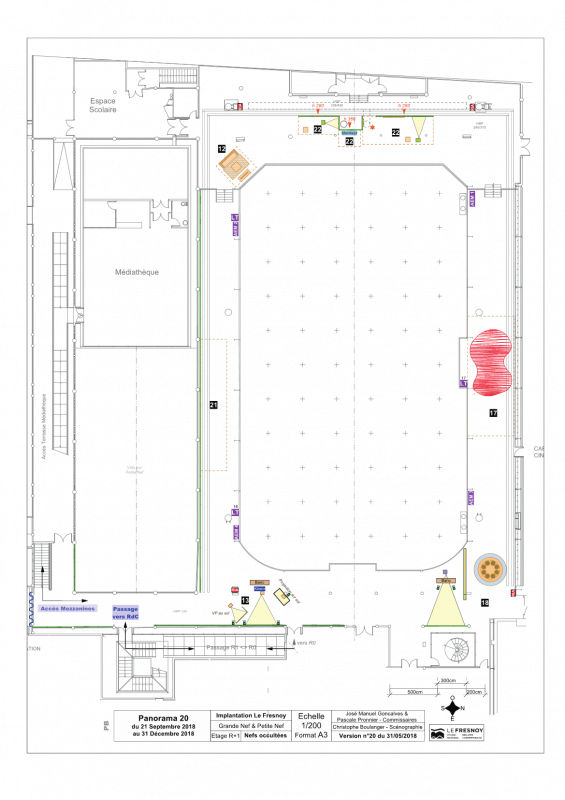

The Fresnoy organizes two to three exhibitions each year, including the annual Panorama exhibition of the students’ works, which are presented to a jury in June and to the public in September. Exhibitions take place in the original part of the building comprised of the two halls of the leisure complex (see installation plan of the exhibition Panorama 20, Figure 1. and Figure 2.). On the first floor, the Grande nef is surrounded by a hallway‑like mezzanine which offers additional exhibition space and permits an interesting view on the exhibition from above26. The two halls are covered by a very high roof with a large glass window that normally floods the space with light but which is sealed off for exhibitions. The space can be modified by temporary walls that are installed and painted grey for each exhibition27 (in yellow on the floor plan). It is therefore possible to adapt the space to the needs of the works. In the case of the exhibition Panorama 20, some works were isolated in boxes (those by Thomas Garnier, Egor Shevchenko and Juan Pablo Villegas), while others made use of a more open space (those by Thierry Fournier, Hugo Deverchère, Vasil Tasevski, Clement Villegas and Chiara Caterina). A special cabinet was created for the exhibition of several works by Joachim Olender, a student at the Fresnoy between 2010 and 2012 who was invited to Panorama 20 to present the artistic part of his ph.d. research. Most of the 24 first‑year students’ produced films were shown in a small cinema space that could be entered through the main hall.

Figure 1.

Layout of the exhibition Panorama 20, ground floor, Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains, 22.09.2018 – 30.12.2018, exhibition design: Christophe Boulanger, layout: Pascal Buteaux.

Figure 2.

Layout of the exhibition Panorama 20, first floor, Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains, 22.09.2018 – 30.12.2018, exhibition design: Christophe Boulanger, layout: Pascal Buteaux.

The flexibility of the space in which it is displayed is an important factor in the exhibition of new media art. Indeed, the different shapes and sizes of the works, as well as the required conditions for the use of projection technology, call for a space that can be adapted. In her 2006 essay “The Myth of Immateriality: Presenting and Preserving New Media”, Christiane Paul states that this kind of art requires “a space for exchange, collaborative creation, and presentation that is transparent and flexible28”. The interior needs to be adjustable to fit the artworks’ varying scales and meet their requirements for light and sound. The walls and floors may need to be used to hide technology, which is often perceived as unaesthetic. By allowing flexible walls to be inserted within a given space, the Fresnoy can, to a certain degree create the kind of flexibility which is needed for the exhibition of new media art. Such flexibility, however, is not at all rare in contemporary museum architecture. Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, for example, wished to create a space that would be fully flexible and scalable when they were working on sketches for the Centre Pompidou in the 70s. Rogers commented in an interview with the magazine Dezeen, “If there is anything we know about this age, it’s that it always changes. If there is one constant it’s change29”. Ultimately, Rogers wanted the building to be able to adapt to this constant change. He and Piano created large spaces on different levels, each one twice the size of a football field and entirely bare, without any interruption. These spaces were constructed to be fully scalable and adaptable to changing uses through the integration of movable walls. This flexibility became standard in museum architecture in the 90s30. Museums housed in newer buildings are therefore generally able to offer the kind of flexibility demanded by new media art, along with many other works of contemporary art. However, many museums, especially provincial ones, are housed in buildings that were previously used for other purposes, such as family homes of private donors, old city halls or former monasteries. These buildings might be comprised of a series of smaller rooms and cabinets that offer limited flexibility.

Nonetheless, it is not the ability to flexibly arrange its spatial conditions that is innovative and interesting about the Fresnoy. What is interesting here is, rather, the ceiling. Not only the walls but also the electrical and internet wiring can be rearranged for each exhibition according to the floor plan imagined by the guest curator. The Fresnoy has three electrical circuits: one for light sources that are turned on and off every day, one for computer systems that run throughout the exhibition31, and one for sound systems that can be cut in case of emergencies, such as fire, that call for evacuation of the building. In addition, a hardwired Internet connection, which is faster and more reliable than a wi‑fi connection, can be brought to virtually any spot in the exhibition space. All this wiring is run through the building’s ceiling and thus remains invisible to the exhibition’s viewers. The technology in the ceiling is very similar to what is commonly used in the performing arts. Theatre and opera stages naturally need to be flexible in order to allow for changes in decor and lighting during a performance. In these settings, metal tubes that hang from the ceiling are used to bring electricity where it is needed on the stage. Since the ceiling is entirely in the dark, this technology is invisible to the spectator. At the Fresnoy, the exhibition space becomes to a certain degree a stage for the exhibition of art. The flexibility of the space is thus not limited to the possible rearrangements of its physical walls but also benefits from the ability to adaptively distribute electricity and Internet wiring.

The parallels between the exhibition space and the theatre continue. Most exhibition spaces are typical ‘white cube’ spaces, designed to be bright and flooded with light, ideally natural light coming from the ceiling. Whenever necessary, electric ceiling lighting and spotlights can be added. The white walls increase the brightness of the space by reflecting the light falling upon their surface. Good lighting is of course necessary to allow spectators to see the art in proper conditions, but the brightness also adds to the museum atmosphere while it awakens and stimulates the spectator. On the contrary, the Fresnoy offers a space that is mostly dark: the windows are sealed off, the lights are dimmed and the grey wall colour is chosen because it reflects little light. These conditions are also necessary to allow spectators to see the works, many of which use video projectors32. As in a theatre, where the only light comes from the stage, the spectator is placed in a dark space where all light either comes directly from or is directed towards the works of art. The use of light yet again places the exhibition space of the Fresnoy in the proximity of the performing arts, making it like a theatre for the exhibition of art. Christophe Boulanger, scenographer of the Fresnoy, also describes the space of the Fresnoy as an “exhibition theatre”. As in a theatre, the experience originates in a dark space to which light is introduced later33.

In a typical ‘white cube’ exhibition space, works that use video projectors or involve loud sounds are generally placed in specific rooms. Special ‘black boxes’ are created to house these works and provide the necessary conditions for video projection, but such arrangements also remove the work from the flow of the exhibition. While in the main exhibition space the spectator sees an entire room of works that the curator has chosen and placed together for their thematic interrelation and which thus create a semiotic space, the works shown in ‘black boxes’ are cut out from this space and placed to the side. In spaces like the Fresnoy, it is possible for several works of new media art to be seen and possibly heard together; works can thus influence a spectators’ reading of other works and participate in a collective creation of meaning of the exhibition as a whole. While in the typical ‘white cube’ an effort is made to ensure optimal viewing conditions for works that require a lot of light, here an effort is made to optimize viewing conditions for works that are best placed in the dark.

Arranging an exhibition space in this manner, however, also entails certain ambiguities. Not nearly all of the works that are exhibited at the Fresnoy use projection technology calling for a dark space. Photographs are regularly exhibited, along with installations that are better viewed with a fair amount of light. In order not to negatively influence the presentation of other works, these pieces are also placed in relatively dark spaces. This was the case, for example, for the work The Crystal & the Blind by Hugo Deverchère34 [Figure 3.]. Being interested in space flight and space research, the artist re‑created a laboratory inspired by two research projects, Biosphere 2 and the nasa Ecosphere, both of which aim to create autonomous terrestrial ecosystems. Deverchère used materials that he had found at the base of Biosphere 2 in Arizona, combining them with living beings such as plants and fish in order to recreate the atmosphere of a futuristic research lab. An artificial intelligence, nourished by the Biosphere 2 archives and fictional narratives collected by the artist, writes a new narrative archive influenced by data collected in the laboratory. The artist wanted to create a highly transparent and open space for his work. He used many translucent materials like glass and plexiglass that reflect light and contribute considerably to the aesthetics of the work. Originally, he wanted The Crystal & the Blind to be displayed surrounded by transparent pvc strip curtains35. This, however, would have negatively affected the presentation of the works using video projectors that were installed behind Deverchère’s work in the exhibition. Therefore, the curator and set designer decided together with the artist that only two sides of the cubic construction should consist of pvc strip curtains and that the two other sides should be made of drywall. In this case, the work was ultimately changed, as the artist’s vision was adapted to the conditions of the exhibition.

Figure 3.

Hugo Deverchère, The Crystal & the Blind, multimedia installation, 2018, Production: Le Fresnoy - Studio national des arts contemporains.

Similarly, Marie Lelouche, a graduate from the year 2017, wanted to exhibit her work Blind Sculpture [Figure 4. and 5.] in a very bright space. Over several years, the artist carried around a 3d scanner to collect 3d images of architectural fragments. Unsatisfied with how they were visualized in software, she searched for a new form, either physical or digital, in which to store her archive of architectural fragments. In Blind Sculpture, thanks to an augmented reality device comprised of a smartphone equipped with a Kinect motion sensor, the spectator can watch these forms float through space, get closer and finally encircle a 3d‑printed high density polystyrene sculpture. The piece was exhibited as part of the Fresnoy Panorama 19 exhibition in 2017 and has been exhibited several times since then in France and Italy. When I curated an exhibition of this piece at the Galerie Commune as part of the foor exhibition programme, the artiste and I discussed the exhibition conditions and lightning of the piece. For the augmented reality programme to work properly, the space had to look exactly the same throughout the entire period of display. It was very important that there were no shadows or reflections of light on the walls that could have interfered with the programme. It was therefore necessary to obscure some of the windows of the space. In the end, Lelouche was very satisfied with the exhibition conditions at the Galerie Commune because the space offered a large amount of natural light, which complemented the white, padding‑like aspect of the sculpture36.

Figure 4.

Marie Lelouche, Blind Sculpture, high density polyester sculpture and smartphone with augmented reality application, 2017, Production: Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains.

Figure 5.

Marie Lelouche, Blind Sculpture, high density polyester sculpture and smartphoe with augmented reality application, 2017, Production: Le Fresnoy ‑ Studio national des arts contemporains.

The difficulty of exhibiting art that is better suited to brightly lit spaces at the Fresnoy is further exacerbated by other characteristics of the space. While the colour of the walls has been selected to absorb light, the ceiling is nonetheless white. Thus, the light that is emitted from the works is reflected by the ceiling and spread over the space, making it very difficult to satisfy the varying needs of different works of art37. The Fresnoy, like most venues that exhibits works involving different media, is therefore faced with a very difficult decision. Here, the decision was made in favour of suitable screening conditions for video projectors and projection screens, which are used in the majority of the exhibits, to the detriment of works better suited to brighter conditions.

Administration and equipment

Similarities between the performing arts and exhibitions at the Fresnoy can not only be found in the treatment of light but also in the profiles of those who work on the installations of exhibitions. The Fresnoy has a team of 49 employees38. The exhibition department has only two permanent employees: an artistic director, who works hand‑in‑hand with the curator and set designer, and a stage manager, who coordinates the teams installing the exhibition and is in charge of the technological equipment. The exhibition department is supported by other departments, such as the departments of communication and education and the technical department, as well as by a team of independent workers who often also work with theatres and opera houses in the region (including the Opera of Lille, the theatre La Rose des Vents in Villeneuve d’Ascq and the Phénix national theatre in Valenciennes). The Fresnoy thus works with audiovisual engineers, light technicians, sound technicians, electricians, stage designers and other professionals trained in the performing arts. In its over 20 years of existence, the institution has been able to build an important network of independently working professionals with a variety of qualifications who are able to support the Fresnoy’s core team when needed. While it can easily be assumed that most museums rely on outside help for the installation of exhibitions, the type of qualifications required of these workers can be quite different from what is required for working with new media art. Thus, besides those with experience in theatre, the Fresnoy also collaborates with individuals who have a deep understanding of the artistic or technical aspects of new media artworks, including artists, some of whom are former students of the Fresnoy, and computer specialists.

The period required for the installation of artworks and exhibition design (including the arrangement of temporary walls and design of light, sound and lettering) is quite long. For Panorama exhibitions, two weeks are reserved in September when the works have already been fully built to finish installing lights, finalize the walls and paint jobs and attach wall labels and other inscriptions. This period is also serves as a kind of test phase for the art, in which the works run under exhibition conditions. This is meant to allow potential bugs and malfunctions to be identified and resolved. Nonetheless, during the exhibition, unforeseen technical difficulties regularly arise. This was the case with the work Cénotaphes by Thomas Garnier, an architectural machine that continuously assembles and reassembles small concrete blocks to constructions resembling architectural models. The artist was inspired by ‘ghost cities’, those standardized urban districts made of concrete whose construction has, for varied reasons, never been finished, thus turning their structures into instant ruins. The machine is filmed from the inside by a camera that moves through the installation on a carrier. The installation was broken once by a spectator and had several malfunctions during its exhibition. The artist returned to the site of the installation multiple times to repair the work. He stated in an interview with art students from the University of Valenciennes that “the work is part of my everyday life at the moment. I am obliged to pay attention to it, which is interesting because I am not sure whether it is the work that serves me or I who serve the work39”. The Fresnoy has the advantage of having close relations to the artists and of other individuals who are involved in the creation of the artworks. Thus, as is the case at festivals such as Ars Electronica, the artists themselves can help to install the work and troubleshoot during the exhibition period.

Finally, the Fresnoy also owns a large collection of technological equipment, including video projectors, projection screens, monitors (including several crt monitors, which are becoming increasingly rare), loudspeakers, computers and mp3 players. While certainly not all the equipment corresponds to the latest standards, it is still very convenient for artists and staff to be able to rely on such resources. In other museums, especially smaller ones, gaining access to technological equipment can be quite difficult, despite the fact that it is now possible to rent equipment, and specialized institutions like the Fresnoy or the zkm can loan equipment to support other institutions. For example, for the exhibition Indices d’orient: La mémoire, le témoin et le scrutateur held at the muba Eugène Leroy in Tourcoing (8 October 2016 to 8 January 2017), a large amount of the works used video and projection material was lent by the Fresnoy to the muba. Since many municipal museums in France are funded by the city they belong to, they do determine their own budgets and must have expenses approved by the city council. Especially in the present period of frequent budget cuts, it can be difficult for museums to persuade mayors and council members, individuals who are generally not specialized in the arts, of the necessity to purchase technological equipment. Thus, some municipal museums in France struggle to obtain the necessary funding to replace light bulbs for video projectors. Rosanne Altstatt, former director of the Edith‑Russ‑Haus für Medienkunst in Oldenburg, explained in a 2004 article on the exhibition of new media art that a main difficulty in organizing such exhibitions is the lack of appropriate equipment and knowledge of new media technologies in art museums40. A great deal has changed in this regard since 2004. Digital technologies are virtually ubiquitous; they are more widely available and less expensive than in 2004 and can be rented for a fee. They have thus become more affordable to institutions with small budgets. Nonetheless, obtaining the technological components required for new media artworks, especially those that use cutting‑edge technology that demands highly specific knowledge to manipulate, may still be a problem for some institutions. This is especially true for those institutions exhibiting new media art only sporadically. Such institutions generally do not have staff on hand who can help install and maintain these works, nor can they rely on a network of qualified independent professionals, which may take years to build and requires time to maintain.

Links between collecting, preserving and exhibiting new media art

The preceding analysis of the curatorial practices and working methods implemented at the Fresnoy provides one example of what may be needed when it comes to the exhibition of new media art. Besides having a flexible space, which in most contemporary museum buildings is a given, it is important for institutions to have access to sufficient technological equipment and a large network of well‑trained individuals with specific knowledge for the installation and maintenance of technologically‑driven works. It is not difficult to imagine that such a network is much harder to maintain for institutions that do not engage with new media on a regular basis. Large, specialized institutions like the zkm are able to keep such knowledge in‑house and will therefore have employees who can intervene immediately to help with the preservation and maintenance of works. At the Fresnoy, staff members possess technological knowledge that is sufficient for tasks such as switching works on and off and debugging more minor issues; however, the institution largely depends on its contacts with outside workers, artistes and technicians with whom they maintain a close connection. Being able to access such a network decreases the response time in cases where an intervention is needed to keep a work running and eventually also reduces costs. Institutions that only work with new media art sporadically not only have to work with outside specialists when organizing exhibitions, but they also need to find these specialists first. Even though many institutions employ staff with technological skills, such as audiovisual and electronics engineers, who can install video projectors and sound equipment and bring electricity where it is needed, acquiring access to more specialized knowledge might remain challenging. As Charlotte Morel, head of the department of Visual Arts for the city of Lille, points out in an interview, the exhibition of artistic practices using new media or digital technologies involves a great deal of uncertainty. For Morel, this uncertainty is mainly linked to the ephemeral aspects of these works and the difficulties that one outside the field faces in finding adequate solutions and gaining access to relevant practical knowledge41. She still views “new media art as a world apart” and suggests that, in order to be able to exhibit and collect new media art, one must be an actor or power broker in the world of new media oneself. She therefore states that she could not imagine including new media in a collection she directed. However, she grants that she could imagine licencing new media artworks for a certain amount of time.

Most interestingly, the Fresnoy and most other institutions in the region that most frequently engage with new media art do not entertain a collection. Even though the Fresnoy produces around 50 works a year, owns the exhibition rights to these works and stores them on site for around two years after the exhibition, it has no collection. In general, many venues specialized in the exhibition of new media art, such as the v2_Institute for the Unstable Media, as well as festivals specializing in such exhibitions, also do not house collections. Among these institutions, the zkm seems to be an exception, with its collection of around 8,000 works of 20th and 21st century art in a variety of genres and media, including painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, photography, film, video and installation, as well as their unique, world‑spanning collection of computer‑based installations, video tapes and video installations42.

Collecting and organizing exhibitions are not only two pillars of the art museum an institution; they are also interconnected and mutually dependent. While most museums organize temporary exhibitions, for which they borrow works from other institutions, from private collectors, or from the artists themselves, these exhibitions may also be intended to show and give value to pieces in the collection. Thus, in selecting themes for temporary exhibitions, museums may naturally choose those into which some of their core works already fit. As the art critic and curator Domenico Quaranta has pointed out, new media art is still rarely collected, with few exceptions depending on the way digital technologies are employed by the artist. Works with a strong object character, such as Daniel Rozien’s mirrors, seem to be easier to sell and more attractive to collectors than works with a very significant technological aspect43. Sometimes, artists whose works have a very strong digital component choose to adapt their works to better fit the expectations of the art market and collectors, or they are forced to adapt them by the collectors themselves. New media installations are also less attractive to private collectors who want to display their possessions in their homes or offices. Digital art, video, installations or performances still have the reputation of being difficult to exhibit in such spaces. Therefore, little new media art is purchased by private collectors, leaving the museum as the main institution that can acquire this type of art 44.

The enquiry concerning exhibition practices in the region Hauts‑de‑France mentioned in the first section of this article also seems to indicate that exhibitions by art institutions in the region Hauts‑de‑France feature a greater diversity of media than are included in the collections of these institutions. This has been confirmed by some institutions in the Hauts‑de‑France. For example, the Musée de Soissons, the Musée du Touquet‑Paris‑Plage and the Musée départemental Matisse had already featured new media art in exhibitions or planned to include it in the future but did not have such works in their collections at the time of the enquiry. Similarly, the Centre régional de la photographie in Douchy‑les‑Mines exhibits photography, installations, sculpture and video, but all items in its collection are physical photographs45. The city of Lille also has a residency programme, the Wicar Prize46, which each year sends three young artists to Rome and gives them access to a studio in the centre of the city. The artists stay in Rome for three months, and the city of Lille pays all travel expenses and provides a production budget. Furthermore, a work created during the residency will be bought by the Wicar Collection. The artists are free to produce any kind of artwork they wish in any medium. However, the collection can only purchase works in ‘traditional’ media, such as painting, photography, drawing, print or sculpture47.

Some collections, such the frac Grand Large Hauts‑de‑France in Dunkirk or the frac Picardie Hauts‑de‑France in Amiens, have a category called “new media” (“nouveaux médias”) in their collections. While the frac Picardie, which has a collection specializing in drawings, includes six videos tagged in its “new media” category, the frac Grand Large has 37 items in this category, namely 30 videos, six works of sound art and one interactive video installation. This work, a video installation by Chilean artist Lorena Zilleruelo, is the only work in a collection in this region which would fall under a stricter definition of “digital art” such as the one provided by Christiane Paul, where “digital art” refers specifically to art that uses the inherent characteristics of digital technologies as a medium and not those works that use it merely as a tool48. Zilleruelo’s video installation, which was produced by the Fresnoy in 2016 and bought by the frac Grand Large in 2017, is a work that addresses the subject of revolt against social injustice and has to be activated by the spectator.

Thus, in Hauts‑de‑France, even though new media art is regularly exhibited, it is very rarely collected. There may, of course, be several reasons for this tendency, including the scientific missions of the institutions in the region and the scope of the specific collections. However, it is also important to consider the difficulties presented by the preservation of new media art and art institutions’ relative lack of specific technological knowledge concerning new media art when attempting to explain this tendency.

Because it is part of a museum’s mission to care for their collections and preserve the works they hold in stock, they are naturally concerned with the longevity of the works in their collection49. Although it is outside the scope of this article treat the subject of the preservation of new media art in the detail the topic deserves, it is important to note that the preservation of this kind of art has long been and continues to be a source of difficulty50 and that, for a number of reasons, these difficulties may prevent new media art from being collected in public museums. The periodic obsolescence of software components and short lifespan of hardware make new media artworks especially ephemeral and vulnerable to change. Much work has been done in the field of new media art preservation since new media art first entered large museum collections in the late 90s and early 2000s (and even earlier in some institutions, such as the zkm). Collaborative research projects – among them the Variable Media Network, Matters in Media Art, Inside Installations and docam51 – have been conducted, and some institutions, such as Tate and the zkm, have offered assistance in preserving these artworks to other collections. Nonetheless, difficulties related to the preservation of new media, despite the fact that some think of them as a “growing myth”52, continue to persist and dissuade collectors from buying new media works.

The main strategies used for the preservation of new media art consist in keeping a supply of relevant technological equipment in storage. This stored technology allows broken hardware to be replaced. The zkm, for example, has several Indigo 2 computers that it maintains in storage in order to keep the work The Legible City (1989‑1991) by Jeffrey Shaw running. However, this approach can only offer remedies in the short and medium term. Eventually, all stored hardware will be used, and even when hardware is stored under proper conditions, some components can become faulty over time. Emulating a specific media environment, meanwhile, allows older code to run on newer hardware. This practice, however, may be seen as altering the relationship between software and hardware maintained in the original work. Digital codes can also be migrated to newer hardware. In this case, the original code is segmented, and each segment is then adapted to a newer media environment. However, this practice not only changes the bond between the work and its original hardware but also changes the immaterial code of the work. Sometimes, when no other preservation method is available – for example, because the work is already too damaged – works can be recreated based on existing documentation and research. Since all these strategies destroy the bond between original code and material, media archaeologists such as the pamal_Group favour an approach to preservation that aims to maintain the work with its original hardware, software and industrial heritage (that is, its technological equipment). This method, which may also include emulation or simulation, involves the creation of a “second original”; in this way, the gap between the recreation and the original work is acknowledged, and the preservationist intervention is clearly exhibited, allowing one to grasp what has been lost in the digital environment as well as in the aesthetics of the work53.

As Jon Ippolito argued in his 2016 article “Trusting Amateurs with Our Future”, traditional methods for preserving art are generally not applicable to new media54. According to Ippolito, the technology necessary for running older digital art “is far more likely to be found in a teenager’s bedroom than a conservator’s lab”, and “even when aware of promising strategies such as emulation, museums and other cultural institutions are having trouble adapting to them55”. In some cases, institutions might work with non‑specialist amateur communities for the purpose of the preservation of their works56. The preservation of new media ultimately calls for a flexible, case‑by‑case approach while requiring specialized knowledge and interdisciplinary and community support. Here, again, it seems that access to a seizable network of contacts, including academics, professionals of different disciplines and amateur programmers, is highly valuable.

Museums have to ensure the longevity and preservation of the works in their collections. In France, collections of public museums are “inalienable”, “imperishable”, and “unseizable” (“inaliénables”, “imprescriptibles” [Article L3111 CG3P] and “insaisissables” [Article L2311 CG3P]). This means that, once it has joined the collection of a public museum, a work cannot be sold, as it can in some other countries. The politics concerning the sale of artworks can indeed differ greatly depending on national legislation and policies. Some American, Canadian and British institutions have recently been prompted to sell pieces from their collections in order to make up for financial losses caused by shutdowns in the wake of the covid‑19 crisis. In Germany, museums and public collections are legally allowed to sell their works, but the ethics and codes of conduct implemented by these institutions prohibit them from doing so. Consequently, German public collections very rarely sell their works57. In France, public museums are not allowed to sell their works, and as a result, museum collections in France are much less flexible than those of countries such as the United States, as Guillaume Cerutti, former director of the Centre Pompidou (1996‑2001), states in an interview with Le Figaro58. When a public museum in France wants to acquire a work for its collection, the acquisition must be validated by a consultative commission59. The expected longevity of the work and possibilities for its preservation are also taken into consideration by these commissions.

The fact that acquisition costs for new media art are often low helps little to encourage their acquisition, given that future preservation costs are uncertain and likely to be high. New media artist and academic Thierry Fournier, for example, estimates that his works will continue functioning for around 10 years without any major problems. Afterwards, maintaining them will require an investment of around the amount of the original production costs. Therefore, he has difficulty imagining the kind of collection that would be willing to invest in pieces like his and, like many other new media artists, has chosen to pursue a different economic strategy. Instead of selling his works, he charges a fee for their exhibition. For him, it does not seem very important that his work will probably not be preserved and may die in the long run60. Many artists, especially young artists, do not project themselves and the existence of their work in the distant future. The idea that their work should be preserved indefinitely seems strange and presumptuous to them (or at least to the artists I have been able to speak to). Of course, sometimes the refusal to inscribe one’s work within a long‑term strategy and the decision to create ephemera instead are part of the conceptual framework of a piece, but this is not always the case. Meanwhile, given that it is their duty to preserve cultural heritage, museums do not work within these temporal parameters. While art centres, galleries and Kunsthallen, not owning collections, can inscribe their activity in this temporal logic and engage in the production of works without having to imagine how they will be preserved for the future, museums – with their collections and mission to care and preserve –cannot. Even though institutions like the Fresnoy consider the preservation and the possibility of exhibiting works in the future during their production, their main focus is the production and presentation of these works, rather than their preservation. While exhibitions of new media art can certainly broaden audiences and raise awareness for this type of art, only the systematic collection, documentation and preservation of new media art will ensure its longevity and allow access to it for future generations.

Conclusion

The use of new media technologies is no longer placed in a niche today. Artists can make free use of the possibilities the digital medium offers to them, depending on what is best suited for the specific message they want to deliver. While more and more institutions have been collecting experiences with these works, thus making it also easier to engage with them in the future, some institutions still are excluded from this development. This is no longer a question of not wanting to engage with new media technologies. All the people I have met and I was able to talk to about this subject, museum staff or collection employees, understand the importance and necessity to collect and exhibit this kind of work. It also seems that size does not matter. There are also many very small institutions with ambitious staff proposing compelling curatorial models for digital art. What seems to be more important is the access to a network of professionals from a variety of specialities or even amateurs offering different kinds of knowledge. The ability to work in close collaboration with the artists or people who are involved in the production process of the artwork also can be an advantage. It also seems very important to have a certain flexibility but it is not all, it cannot be reduced to space and electronic wiring. It also needs a flexible administrative structure and the capacity to release budgets or adapt the collection policy. The digital divide has shifted. It no longer lies between specialized institutions engaging with new media art and a broader art community ignoring it, but it today devises art institutions exhibition and collection practices.

I would like to conclude by pointing out that working with new media does not mean the same kind of engagement for all institutions and for some it is more easy today than for others, for multiple reasons. Having a historical collection that is shown also through temporary exhibitions can be one of the factors that makes it more difficult to deal with new media art. There are many factors at play as regards an institution’s aptitude to exhibit technologically driven art. The ones discussed in this article only show a part of them. Others can come to different solutions for the same problems, perhaps by examining different practices and/or by looking at different institutions. The multiple layers and dimensions of our institutional art world, as well as the multitude of varying characteristics of new media art demands specific solutions for each work and for its exhibition.